The Theater of Coaching

How do coaching styles transform individuals, teams, and countries?

Table of Contents

This is Part 2 of a series on Sport as Theater: The Hero’s Journey. Check out the rest:

Have you ever had someone tell you can’t do something, only to do it so well that they pretended to never have said it? It’s a glorious feeling. To look deep within and find that magic — that spark — that lights a fire no one can extinguish. Not even your own kin.

I’ve been trying to find that spark ever since I was a kid. Whenever I took an interest in something new—a recipe, a workout, a musical instrument—I naively expected my mother to believe in me. Instead, I was greeted with a broken record of you-can’ts. At 16, I wasn’t even encouraged to play around in my own kitchen. “You’re going to burn the place down,” she would say with such disdain and certainty that I felt morally obligated to prove her wrong. Which I did.

So was my mother a coach from hell or did I train myself to turn anger into a motivational trigger? I’m not entirely sure and I don’t think it really matters…

But what is it about the words “you can’t” that makes us want to try harder? Aim higher? Go where no one’s gone before?

You don’t have to be a professional athlete to feel this drive. It’s the same fight-or-flight response that keeps us from dying — and Olympians from losing.

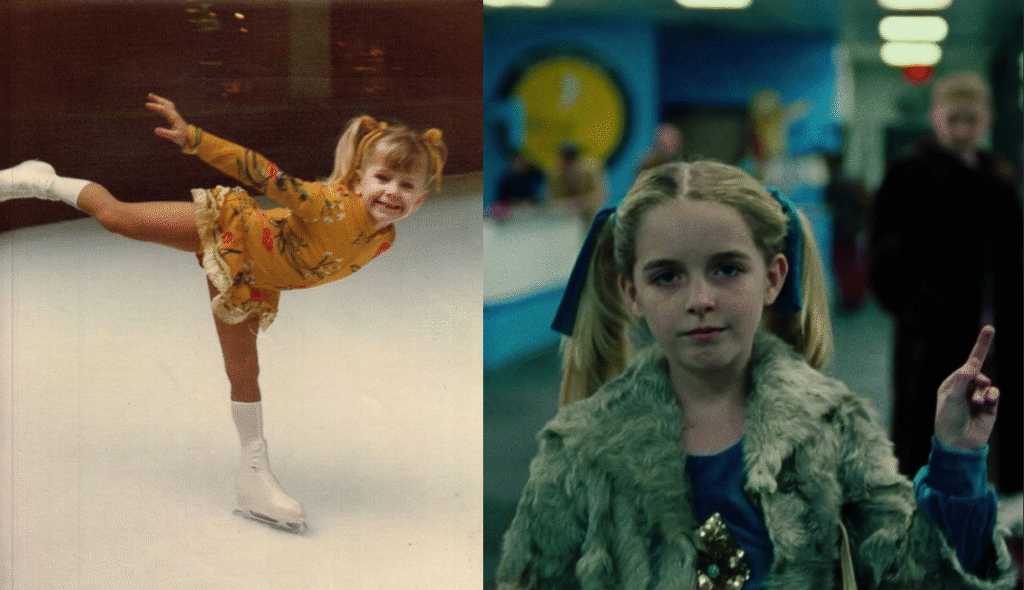

(L) 2x figure-skating Olympian Tonya Harding as a child / (R) Actor Mckenna Grace as young Tonya Harding

I wish I could say I turned every “can’t” into a “watch me”. But I didn’t. While it’s easy to blame family for our embarrassing shortcomings, turns out it’s a little more complicated than that. In sport, as in life, coaching isn’t about finding someone who can magically guide you and shape your destiny. It’s about finding your own potential and ultimately discovering the great unknown:

Do you still have a bit of fight left in you?

Bench the ego

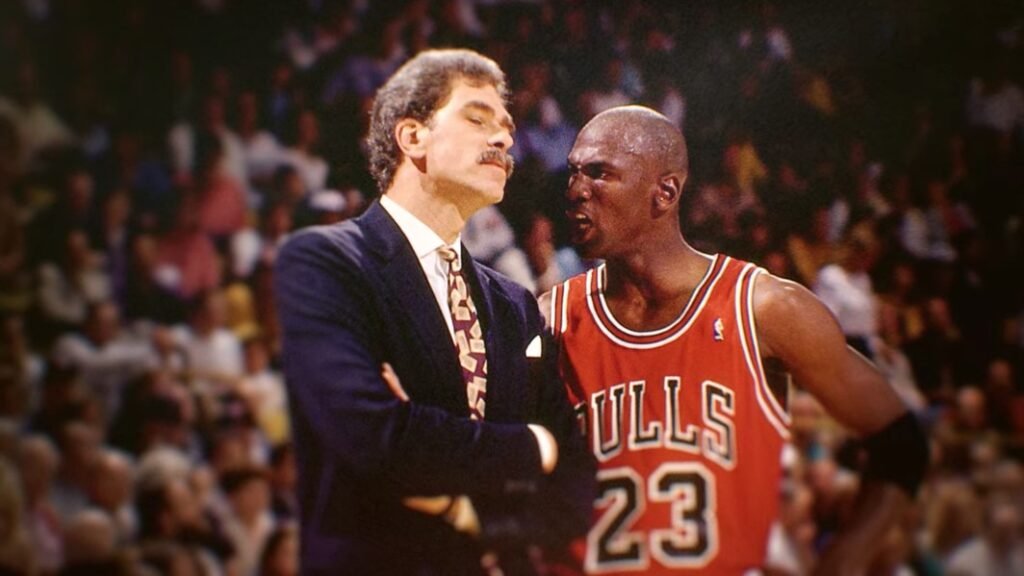

“Michael Jordan used to say that what he liked about my coaching style was how patient I remained during the final minutes of a game, much like his college coach, Dean Smith.” (Phil Jackson | Getty)

There’s a reason why many of the greatest athletes faced extreme hardship at a young age. Poverty, inequality, racism, violence. Talent needs trauma — that’s the impression we often get from watching sports documentaries and movies about our favorite heroes, be they real or fictional. Yet recent studies on the relationship between childhood trauma and athletic prowess reveal a more nuanced perspective. Research and Innovation Lead at the Sport Information Resource Centre, Veronica Allan (PhD, Sport Psychology) observes:

“A closer look at the research shows that it’s not the trauma itself that creates sports superstars—it’s what the athlete brings into and takes away from the experience, as well as opportunities to participate in a supportive sport environment.”

Of course, the coach has the difficult task of creating this supportive environment while challenging the player as an individual — and the team as a collective — to perform at the highest level. For Phil Jackson, who coached the Chicago Bulls during the the golden age of basketball, it all came down to one thing: mindfulness. Unlike Jerry Krause, former general manager of the Bulls — who once allegedly remarked: “Players don’t win championships, organizations do” — Jackson was all about bridging differences between the individual and collective.

In his book, the Zen Master (so-called for his interest in eastern philosophy), talks about his unique approach which deviated from the two most popular coaching styles at the time: the domineering “my-way-or-the-highway” and “the suck-up coach”. He writes:

“I’ve taken a different tack. After years of experimenting, I discovered that the more I tried to exert power directly, the less powerful I became. I learned to dial back my ego and distribute power as widely as possible without surrendering final authority. Paradoxically, this approach strengthened my effectiveness because it freed me to focus on my job as keeper of the team’s vision.”

Phil Jackson, Eleven Rings: The Soul of Success (Penguin Random House)

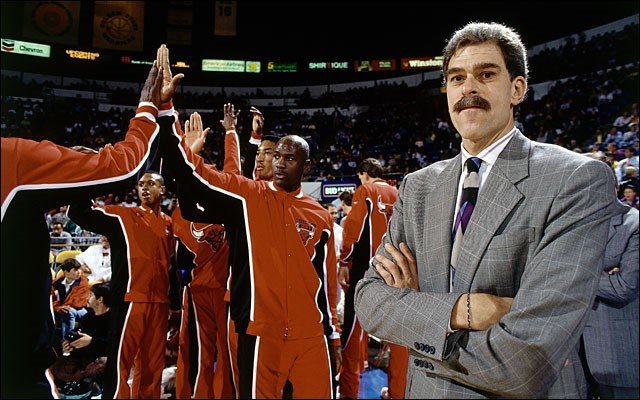

Coach Jackson with the Chicago Bulls | Getty Images

A former pro basketball player himself, Jackson currently holds the unprecedented title of winning 13 NBA championships, two as a player and eleven as a head coach (hence the “eleven rings”). He attributed much of his professional success to mindful awareness, which combined Native American-inspired team-building rituals with sports psychology to unlock the team’s hidden potential.

Through concepts like “the Circle”, Jackson managed to introduce Zen Buddhism and Native American teachings to a team with big personalities, including someone who made headlines for being “bigger than the Pope.” Among other things, it helped Michael Jordan reimagine the team’s leadership structure as “a series of concentric circles” where “nothing could get inside.”

The same mental fortitude and presence of mind that drove the likes of MJ, Scottie Pippen, and Dennis Rodman on a basketball court can be seen in cut-throat competitions outside the NBA. Whether in sport or life, straddling that fine line between confidence and mindfulness becomes part of the test of becoming a hero.

Take Serbian tennis player and avid meditator Novak Djokovic — Olympic champion and the only man in tennis history to win all four majors at once (Australian Open, French Open, Wimbledon, and US Open) across three different surfaces. It’s no surprise that mindfulness comes up routinely in his interviews, a key to overcoming self-doubt in grueling matches that sometimes last up to 5 hours.

In a conversation with La Nacion in 2024, Djokovic also attributed his resilience to his rough upbringing as a twelve-year-old witnessing the horrors of the Serbian war, which ultimately shaped his mentality as an underdog: “For me it was a very important part of my development and as a small child, I was forced to grow up.”

In his book, Phil Jackson similarly talks about using meditation not to suppress anger, but “to transform its underlying energy into something productive.” This is exactly what we see when a resilient player is berated, ignored, or provoked, whether by an opponent or the crowd itself. Professional athletes are no stranger to this attempt at distraction, though few can channel a chorus of boos to fight harder and win.

“I’ve played in a much more hostile environment. You guys can’t touch me.”

Djokovic, Centre Court, June 2024

Djokovic shutting down hecklers after winning, Centre Court

Celeberated tennis coach Patrick Mouratoglou, who trained the indomitable Serena Williams for a decade, reiterates the importance of this mental toughness, attributing it to top-tier performers with a competitive edge. In a 2023 interview with Vogue, he echoed the importance of self-belief and how it separated a winner from a champion:

“All the top 10 players were saying it was impossible to win a Grand Slam because of those two guys [Federer and Nadal], and in came Djokovic, who was 19 or 20, and he said, “I’m going to beat those two guys—I’m going to be number one.” And everybody laughed. I remember journalists writing articles saying, “Who’s this guy? He’s so cocky.” And he answered them. Many years later, he said, “I’m not cocky—I just believe in myself.”

What truth?

While some parents refrain from instilling high self-confidence in their children for fear of “creating a monster,” research shows that it can act as a protective layer against mounting anxiety, crippling doubt, and negative self-talk that naturally surfaces in competitive sport. Through discipline and coordinated communication, children can learn to use self-confidence not for social media vanity, but as a tool to adjust mental and physical behaviors in high-pressure environments. More often than not, it’s what they need to hear when going against their biggest competitor.

Unsurprisingly, tennis legend and 4x Olympic winner Serena Williams developed this unwavering self-belief as a child, thanks to a supportive environment nurtured by a hands-on family that included father and then-coach Richard Williams. Seven-time USPTA coach of the year Rick Macci, who trained five No. 1-ranking tennis players (including Williams herself), once noted of young Serena:

“At 11, she told me she thought she was better than John McEnroe. She said, ‘Did you ever see his strokes? He has terrible strokes. I can beat him for sure.’ It was silly, but she meant it from the heart. And she believed it. A great competitor is borderline cocky and courageous.”

In such instances, belief isn’t meant to convince the opponent or the spectator. It’s meant to help the player acknowledge and overcome deep-seated psychological barriers and remain focused in a “do-or-die” environment. We see the same technique used by professional actors to bridge the gap between themselves and their characters, same as go-getters aiming to win at the game of life. With the right attitude, doubt, too, becomes a teacher.

Family and home

In coaching, this informs a specific kind of leadership style where the team is strategically organized as a family to help strengthen trust, make up for each other’s weaknesses, and deliver big in critical moments. 2x Champions League winner Jose Mourinho, aka “The Special One”, cites this as a motivational ingredient not only for high-performing athletes, but also for high-performing coaches.

In The Playbook, he recalls the time he snuck into the stadium to support his team at the time (Chelsea) during the 2005 Champions League against Bayern Munich. Mourinho was given a two-game stadium ban by UEFA, which he defied by hiding in a laundry basket to see his team, almost passing out as a result:

“We won the game, but it’s not about that. I’m proud of it because I did it for my boys. For your family, you do anything. Even break the rules.”

“I think in all my experiences in football, there is the human side. Team, brother…family. And for me, these are the things that stay forever.” (Jose Mourinho, The Playbook, S1, E3)

The appeal to family and brotherhood isn’t merely an attempt to fill a personal void for the player. It’s a powerful recreation of the hero’s origin story — a reminder of their destiny.

In sport as in life, our sense of belonging has such a profound effect on the way we play the game that it becomes necessary to develop rituals that remind us of home, the familiar nest from whence we came, so we can rewrite our story.

Indeed this is why playing the game in one’s own country is considered “a home advantage”. The curious phenomenon exists in various sports, including soccer, basketball, hockey, baseball — each reporting a winning rate of 69, 63, 59, and 54 per cent, respectively, when playing at home. We see the exact same mechanism in theater and live storytelling whereby the actor’s environment becomes critical to the recreation of events and the process of mythmaking. In his memoir, legendary actor Al Pacino recalls such an experience during his stage performance in Richard III which was set against the backdrop of a beautiful old Gothic cathedral that felt “portentous”:

“When we started performing the play there, I was getting five or six curtain calls a night—each time I would take my bows, stand in the wings, and then return to the stage just to bow again—and not because I was so pretty. It was because the audience had an experience watching that production. It had them. It worked because we had the ambiance of the church; the austerity of that atmosphere brought it to life. And it never worked that well again.”

Al Pacino, Sonny Boy (Penguin Press), 2024

✌️ Like it? Share it. ✌️

As in sport, the “family” theme shows up in various incarnations throughout our lives, either through allies, friends, teachers, or retired professionals who sometimes act as a surrogate family for those of us who never had the support and guidance we needed. This is critical for it helps us learn to trust again. To fight again. It’s what makes pep talks so crucial to team work — for turning “me’s into we’s” — and it’s what permeated the famous monologue in the 1999 sports film Any Given Sunday. In an interview with Byron Scott, co-star Jaimie Foxx recalls the humble tip to he gave the “Scar-Father” Al Pacino right before his widely quoted motivational speech:

So I went up to him and I said, “Mr. Pacino, can I speak to you?” You know, humbly. He said, “Yeah.” I said, “When you’re talking to them, you’re not that coach — you’re a father. A lot of these guys out here came from broken homes, came from the hood, didn’t have no father in the household. Our coach — and anybody could tell you, Byron Scott, anybody — can tell you that our coach was basically our father figure, because they were with us more than our parents.” I said, “So when you make that speech this time, talk to them like you’re their daddy.” Oliver Stone said: “And action!” He says, “Every inch…” Oh, he killed it. “And you fight with your fingernails!” I can’t — and when they put the camera on me, I was like, “Shit!” So that was a monumental time in my artistic life.

Jaimie Foxx on The Byron Scott podcast

“Either we heal now—as a team—or we will die as individuals.” (Any Given Sunday, 1999)

Playing with heart

Although trust is fundamental in every team, it cannot be cultivated the same way across every sport or geographical region. Much of this has to do with the history of the game itself, including the political connotations attached to it. Nowhere is this more obvious than the reclamation of mainstream sport in once-colonized territories, such as cricket in South Asia — where winning became synonymous with beating someone at their own game.

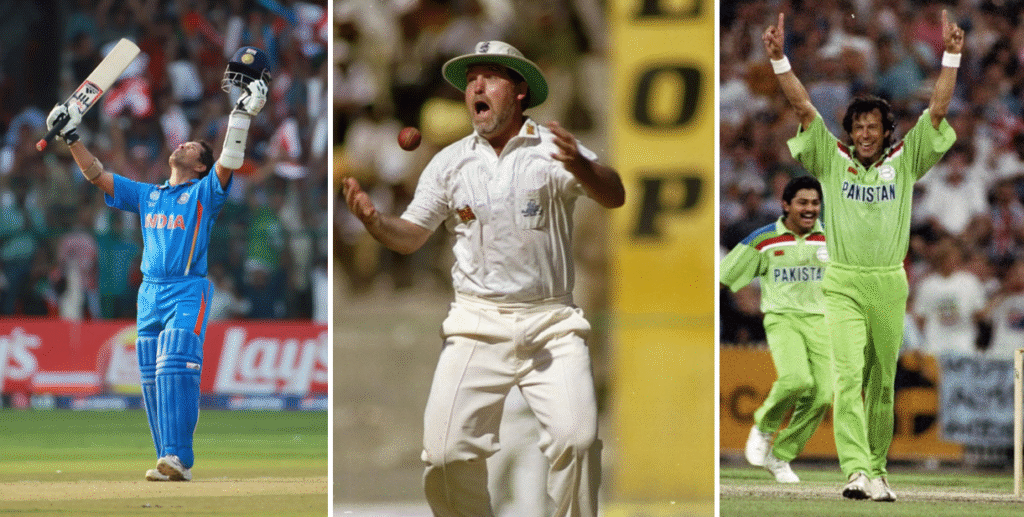

Nineties cricket: (L) Indian cricketer Sachin Tendulkar (M) English cricketer Mike Gatting (R) Pakistani cricketer Imran Khan

This was further complicated in post-apartheid South Africa where the predominantly-white rugby team, the Springboks, had the unprecedented challenge of shedding an identity that became synonymous with apartheid. This was one of many challenges tackled by South Africa’s first democratically elected president and first black head of state, Nelson Mandela.

The unlikely alliances forged during the 1995 Rugby World Cup defined an exceptionally rare form of transformational leadership that set a benchmark for coaches around the world. It also marked a turning point for the Springboks who stopped playing to win and started playing for freedom.

Despite the history of the game and what it represented at the time, Mandela reached out to Springbok captain Francois Pienaar in an effort to unite “the rainbow nation” — a heroic act that not only marked the beginning of a unified South Africa, but led to the country competing in and winning its first ever Rugby World Cup. Nearly two decades later, Pienaar recalled the historic moment on BBC and shared how Mandela inspired him to make changes that led his team to victory:

“I mean, I was just incredibly emotional. If you know our history, rugby was for the white people in South Africa, predominantly the Afrikaners. In the years of apartheid, it became a symbol of hate for the black people — which you can understand. When he [Mandela] walked into the dressing room wearing Springbok on his heart, it was just — wow. He just stood there and said, “Good luck, boys,” and he turned around and… my number was on his back. That was it for me. I couldn’t sing the anthem because I knew I would cry.”

(L) Nelson Mandela with Springbok captain Francois Pienaar, 1995 Rugby World Cup | (R) Morgan Freeman and Matt Damon in Invictus

You may recognize the historic moment in the 2009 Clint Eastwood-directed Invictus. Later in an interview, actor Matt Damon (who played Pienaar for the big screen), echoed Pienaar’s sentiments when he described his own meeting with Mandela, accompanied by his two daughters, recalling:

“The most incredible part of the experience was when we were waiting in the hallway to be ushered in for our few minutes with him; I was holding Isabella when she asked, “Daddy, who’s behind that door?” I don’t know if she could feel my heart beating faster or if it was something else, but she seemed to sense that someone very special was on the other side. And we walked in and neither of the two little ones took their eyes off him, particularly Gia, who was 8 months old at the time. It was extraordinary. So much so that a child who just doesn’t have a dog in the fight — you know, with no agenda — was absolutely aware that there was something special happening.”

The Warrior

(L) The Springboks win the 2023 Rugby World Cup | (R) Springbok Captain Siya Kolisi with coach Jacques Nienaber

Mandela’s looming presence can be felt to this day in the way the Springboks play the game — with accountability, selflessness, and breathtaking teamwork powered by resilience. In the years that followed, the idea of “playing with heart” became so foundational to the spirit of South African rugby, that it led to the idea of a South African “warrior” based on the country’s unique history and multiracial demographic. Here’s how former Springbok and beloved rugby coach Rassie Erasmus describes it:

The same innovative thinking that united a divided South Africa in 1995 continues to play a critical role in the Springboks’ tactical and strategic gameplay, currently making them the reigning 4x World Cup Champions and the only team in history to win half of the Rugby World Cups they’ve participated in.

Rassie, who played a critical role in coaching the victorious Springboks in recent years, along with longtime friend and fellow coach Jacques Nienaber, became known for his technical and innovative approach to leadership, which includes immersive role-play to help players improvise in cut-throat moments, accompanied by sage advice like: “Don’t be an entitled dick like I was as a player.”

Soon he gained a reputation for empowering players to think on their feet, a process that sharpened his own “hunches” about the game. In his memoir, he quotes Nienaber who witnessed Rassie’s bizarre “foresight” take shape on and off the field:

“Over the past 30 years of working with Rassie, I’ve become used to his hunches and how accurate they are. I’m a man of science, and this is something I can’t explain. On the day we selected the team he said to me we must pick Morné (Steyn). He said it wasn’t a hunch; he could see it. […]

The video shows the score is 17-5 to New Zealand in the 32nd minute. I then point the camera back at Rassie. He says, ‘The final score will be 31-22 to New Zealand, and after this you can call me Nostradamus.’

We left it there and went outside to have a braai, forgetting about the game. Two hours later, the game had finished, and Rassie suddenly remembered his prediction. I looked it up. Same score.

So when Rassie said he could ‘see’ Morné kicking the final penalty, I knew what he meant and we brought him into the squad.”

In a conversation with legendary rugby player Os du Randt, Rassie also shared the importance of being honest with the players and grounding them through “leveling” rituals, similar to those in the army: “The first thing they do is take you to the barber, and suddenly we all look the same—everybody’s hair is cut. You don’t recognize the guys. But it also feels like that levels everybody, and it feels like, okay, now we’re all in this together.”

Today he is credited for introducing a wave of changes to the team, changes that have paid off sweetly, including the decision to make Siya Kolisi captain. Kolisi is the first black man to hold the title, consistently leading the Springboks to victory in the last two Rugby World Cups (against England and New Zealand).

In keeping with his belief in open dialogue, Rassie later revealed “the nastiness” that pervaded the announcement, revealing: “I lost a lot of friends when I made Siya captain. Before the World Cup, my daughter’s friends’ parents would say, “Tell that fucking father of yours to stop sucking up for a paycheck!” alluding to racial tensions that continue to threaten South African unity, even to this day.

Springbok captain Siya Kolisi and coach Rassie Erasmus | Image Source: Bona

Unlike traditional coaches who develop a strong aversion to the press, the “maverick” coach extended the same openness to the media whom he once considered “the enemy”. The tactful relationship with the media through his advocacy of teamwork and the #StrongerTogether campaign, subsequently curtailed provincial tensions around various clubs in South Africa which kept the message of oneness alive during attempts to politicize the sport.

In some ways, a great coach reflects the thousand lives of the hero, taking on new challenges to serve a purpose higher than the game. This is why in many parts of the world, coaching isn’t just about winning or breaking psychological barriers. It’s about playing your part in a story that’s greater than any individual, team, club, or organization.

“I’m addicted to the unity in South Africa,” Rassie said recently.

“I’ll keep chasing that for the rest of my life.”

This piece is dedicated to Professor Victor Shea.

🎬 Cool stuff referenced in this piece: I, Tonya by Craig Gillespie, Eleven Rings: The Soul of Success by Phil Jackson and Hugh Delehanty, The Playbook: A Coach’s Rules for Life by Netflix, The Matrix by the Wachowskis, Kill Bill by Quentin Tarantino, Any Given Sunday by Oliver Stone, Invictus by Clint Eastwood, Chasing the Sun 1 and 2 (a SuperSport documentary), Rassie+, a podcast by Smashsport (YouTube), and Rassie: Stories of Life and Rugby with David O’Sullivan. Enjoy!

💭 Leave a comment!

Thank you for reading. Join the Backstage Newsletter for new posts every week!