What is the Haka: Ritual, Remembrance, and Resistance

What happens when sport, politics, and culture collide?

Table of Contents

This is Part 3 of a series on Sport as Theater: The Hero’s Journey. Check out the rest:

Ha Ka

Breath Alight

“Te Rauparaha was a great chief of Ngati Toa Rangatira.

He composed the Māori haka Ka Mate Ka Mate.

One time he was hidden inside a pit while running away from the enemy.

A woman sat upon the entrance in order to conceal his whereabouts.

On the arrival of the enemy, twice they approached the pit, and the second time they left.

The wife is referred to as the hairy man, who made the sun shine again.

From this event, the haka was created.”

Narrated in All Blacks with Wetini Mitai-Ngatai

“I step upwards, I step upwards. The sun shines again.” Source: YouTube

The voice of skies torn asunder. The pulse of creation. The first breath of life.

As a thousand-year-old cultural tradition, the haka remains to this day one of the most spine-tingling forms of oral history. From a performance lens, it isn’t just a “priming” ritual that regulates the performer’s thoughts and emotions prior to an event. It is a testimony of all that was, through the visceral narration of breath and body.

The haka is, in short, a cultural marvel for some—and a way of life for others.

Of course, it’s not the only pre-game ritual that permeates sport and culture. From the patriotic pageantry of national anthems, to the pyrotechnics of hype-building, to the symbolism of the Olympian torch-bearer, sporting events offer a treasure-trove of rituals worthy of analysis.

Yet there’s something about the Māori haka that conveys the sanctity of ritual through the holy trifecta of song, symbolism, and repetition. Like all masterful performances, it is at once humbling and spellbinding—a story as old as time embodied seamlessly in sound and flesh. It is oral history at its finest and it’s what makes ritual a vital part of the hero’s story, especially in the theater of sport.

All Blacks and haka

Source: World Rugby

Popularized in mainstream media by New Zealand’s national rugby team (the All Blacks), the Māori haka is a ritual typically performed pre-event, in sport and in life, to mark a significant moment. For more than a hundred years, the All Blacks have performed a haka prior to every match, building solidarity within the team while inviting the other side to accept a challenge or message. The women’s rugby team (the Black Ferns) perform their own version of the haka called Ko Uhia Mai.

However, New Zealand (Aotearoa = “land of the long white cloud” in Māori) is not the only country known for its haka. The performance is also common to Pacific islanders and Polynesian people with their own unique cultural interpretation, including Samoans, Tahitians, Fijians, Hawaiians and Tongans.

Although haka vary depending on context and situation, they all follow the homogenous structure found in their respective mythologies. In Māori culture, haka performers may stomp their feet in synchronous motion, emulating the physical gestures, rhythmic breath, and vocal chants of their ancestors as a way to communicate with and through the body.

Despite the choreographed motions, each haka tells a different story—aligning the performer’s intention and emotions to convey the fullness of a unique message.

For centuries, the haka has remained an important tradition both for the Māori people and New Zealanders, many of whom grow up learning it as a rite of passage. Ka Mate is perhaps the most widely known of all Māori hakas, alluding to the celebration and triumph of life over death, which makes its reception equally poetic: “Ka Mate, Ka Mate, Ka Ora” translates to “I die, I die, I live.”

While some erroneously refer to the All Blacks’ haka as a literal “war dance”, the Ka mate haka was originally composed as a short haka known as ngeri. Researchers in the Cognitive Science department at Macquarie University explain:

“Ngeri are unlike haka taparahi (ceremonial haka) in that they do not have set actions, ‘thereby giving the performers free rein to express themselves as they deem appropriate.’”

Like all live storytelling, the haka courses through the voice and manner of those who perform it—and lives through the memory of those who bear witness. It’s a reciprocal arrangement honoring the meeting of two forces, which in turn reflects the duality and oneness that permeates much of Māori mythology. In a particular address to the All Blacks, internationally renowned kapa haka expert Wetini Mitai-Ngatai observed:

“It’s an honor to receive the haka. Even though it’s very ferocious, I suppose the way you deliver it, you’re honoring those opponents that you come up against.”

Performing the haka

The Tika Tonu haka (“earth shattering”) is about a boy’s transition to manhood | Source: YouTube

While most people around the world know the haka from the All Blacks, it’s a ritual prevalent across all Māori life, from welcoming someone to celebrating birthdays to honoring the deceased. Even in rugby, Ka Mate is not the only variant of the haka performed by the All Blacks. In 2005, the team introduced Kapa O Pango, performing it for the first time against South Africa in Dunedin. Composer Derek Lardelli explains the meaning behind it:

“Kapa O Pango is about building your spiritual, physical, and intellectual capacity prior to doing something very important. There are haka that use weapons—those types of haka are war haka—but this haka, in particular, is not a war dance. It’s ceremonial. It’s about building the person’s confidence inwardly, their spiritual strength, and then making that spiritual strength connect through the soul and come out through the eyes and the gestures of the hand. So it’s a preparation of your physical side as well as your spiritual side.”

Derek Lardelli, Kapa O Pango composer | Source: All Blacks YouTube

Among the more obvious aspects of the haka is its marvelously coordinated expression of physicality and movement communicated viscerally through posture dancing: bulging eyes (Pukana), tongue-bearing (Whetero), side-to-side movement of the hands (Wiri), the stomping of feet (Waewae takahia), rhythmic breathwork, etc. While some of these gestures may be used to intimidate the other side in certain kinds of war haka in specific situations, the meaning behind them is unique to each tribal group, environment, and intent.

In some ways, this is similar to the way we all use body language to express and interpret deeply held values, thoughts, and emotions, though for most people, body language tends to be deeply unconscious.

Some aspects of the haka originate from creation myths, such as Wiri which signifies “the quivering appearance of the air on hot summer days”. The allusions are evocative and manifold.

According to Māori legend, wiri (the movement of the hands) comes from the dance of Tane-rore—“he who was born of the Summer Maid and claimed Ra, the sun, as his father.” The myth goes: “This light, rapid movement is the foundation of all haka. The hand movements represent Tane-rore’s dance.”

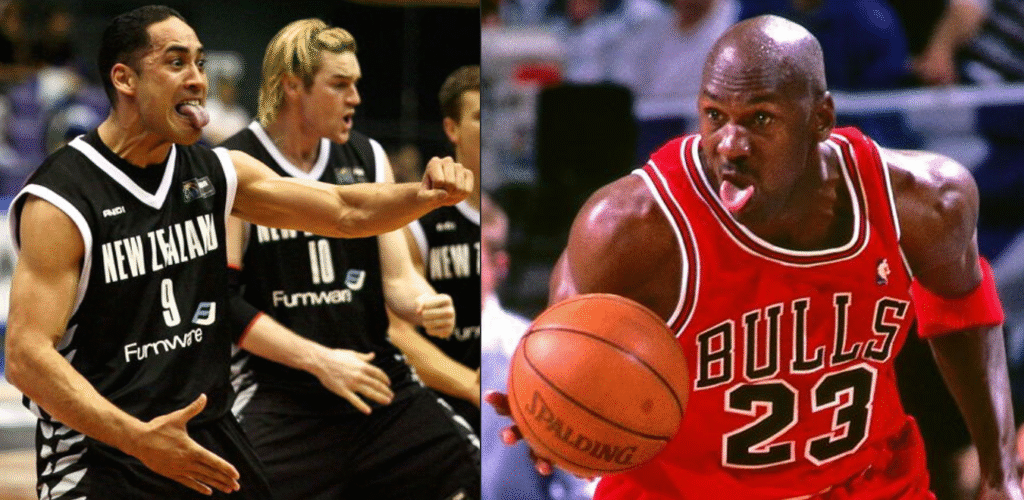

Others, such as “whetero”—the act of sticking out one’s tongue during haka—draws considerable attention in the media for its “non-normative” display in Western societies, where social behaviors are often ritualized to suppress, repress, conform, and separate mind from body. Frequently misrepresented in the media as “intimidation”, whetero symbolizes a man’s virility whereby the tongue represents the phallus, its meaning dependent on the situation.

Certain aspects of the ancient haka, such as the poking of the tongue, become even more fascinating when you consider how they tend to appear naturally in other contexts. This is particularly evident in competitive sport where the body and mind, trained to work together in high-pressure moments, result in intuitive expressions by an athlete “in the zone”.

(L) Paora Winitana of the New Zealand “Tall Blacks” (basketball) leading the haka against Australia, 2006 | (R) MJ’s signature “tongue” move

In his award-winning book chronicling the life of the man, the myth, the legend—Michael Jordan—Roland Lazenby reflects on the NBA champion’s peculiar “tongue” display which became part of his athletic brilliance:

“At this exact moment, the tongue falls out of his face. For ages, warriors have instinctively made such faces to frighten one another. Perhaps there’s some of that going on here, or perhaps it’s just what he has said it is—a unique expression of concentration picked up from his father. Whatever, the twenty-two-year-old Michael Jordan gains full clarity now, flashing his tongue at the defender like he is Shiva himself, the ancient god of death and destruction, driving the lane.”

Roland Lazenby, Michael Jordan: The Life

Perhaps the same could be said of an artist—pianist, singer, guitarist—who seems to go through similar motions during a performance that demands the whole rather than a part. The body becomes an instrument, and the message, a labor of love. Take it from legendary actor Al Pacino, who summarizes his entire life’s artistic work as: “Finding a way to bring something into life so it can go through me.”

The more you pay attention to the theatre of meaning-making activity, in sport or in life, the more you’ll find that most of us are either trapped in our minds or our bodies. Perhaps that is one reason why the haka speaks to so many of us—it combines the best of both worlds. Like a forgotten language, it pokes at something distant yet intimately familiar.

Reactions to the haka

USA vs. New Zealand, FIBA, 2013 | “The faces of the USA players define culture shock,” writes one commenter | Source: YouTube

As with any cultural rituals, it’s not uncommon for audiences to misread the haka due to a general lack of knowledge or limited exposure to non-Western ways of life. But quite often you’ll see reactions laced with perplexity and curiosity, presenting opportunities to learn and share.

Indeed, in many cases, the haka even inspires the other side to tap into the same symbolic language to respond. The reciprocal nature of the haka has given birth to several such reactions in rugby, perhaps the most popular one being England’s response during the 2019 Rugby World Cup semi-final. Whereas opponents usually form a straight line during the All Blacks’ performance, in this instance the English rugby team formed a “V-shaped” defense, crossing the halfway line so as to accept the All Blacks’ challenge.

(L) England rugby team responds to the All Blacks’ haka | (R) English Captain Owen Farrell accepts the challenge

When asked about the arrow-like “V” formation, English rugby captain Owen Farrell later explained: “We wanted not to just stand there and let them come at us.” The V response was generally well-received by New Zealand fans, as well as most Māori people who expressed their enthusiasm for the team’s engagement with the haka. According to haka expert Tapeta Wehi:

“People have to understand more what the haka is about. People think what they are doing is disrespectful. But if you ask Māori, they’ll tell you that’s what it’s all about. It’s laying a challenge and if the other team want to challenge you back, then it’s all good. That’s what it is all about.”

England was nevertheless fined for crossing the halfway line and breaching “cultural ritual protocol”. This was not the only time the haka triggered an unusual reaction on national television. In the quarterfinal match between Ireland and New Zealand, Irish supporters drowned out the haka by banding together to sing the Irish folk song Fields of Athenry, prompting the Irish team to take a step forward as their native ballad echoed throughout the stadium.

From a sociological perspective, the intervention of the Irish audience conveys the important role of the audience wherein “failure to regulate contact involves possible ritual contamination of the performer”. In other words, rituals such as this draw attention to the power of the spectator whose willingness to engage becomes central to the ritual. As we see so prominently in live theater, it is this reciprocity between actor and audience that ultimately contributes to the “realness” of what is presented.

“Rather than being a one-way performance activity from performer to audience, or even a call-and-response activity, haka is ‘a conversation in which the audience is explicitly involved’.”

Haka’s dynamism can be clearly felt in interactions where the message is not only spectacularly conveyed, but also received and responded to in equal measure. This is particularly common in “pre-battle” rituals as a way to present and accept a challenge, where the response allows both sides to fully embody their roles. But that’s just one part of it. The vibrant symbolism of the haka may also enable emotionally charged exchanges of mutual respect prior to the main event, enabling displays of sportsmanship and a shared acknowledgment of the event.

An excellent example from the sporting world comes from 2020 when the All Blacks commemorated Argentine football icon Diego Maradona during the haka when playing against Argentina. The gesture was returned in 2022 by Ireland when the Maori All Blacks performed an emotionally charged haka as a tribute to the late NZ rugby player Sean Wainui, preceded by the Irish team’s symbolic acknowledgement and respect for their opponent

That’s why rituals matter. They help in the co-creation of social reality and stand at the heart of meaning-making activity. At the end of the day, ritual is a language of consensus.

Language of the game

Source: The Haka Party Incident

A big part of the haka is, of course, the literal language in which it’s performed—representing ancestral history and lived experience that goes back perhaps a thousand years. This is why language extinction is political in nature. It eviscerates not only the voice of a people, but their very existence and ways of being. Rebecca Schneider writes that history is co-created not only through textbooks but through rituals of repetition and remembrance.

In her seminal work Performing Remains, she reveals how Western logic typically undermines “the event” in favor of “visible remains” in order to create an architecture of power over memory—architecture that is continually challenged by cultural, racial, and ethnic minorities through spoken language, oral narratives, and the performing arts.

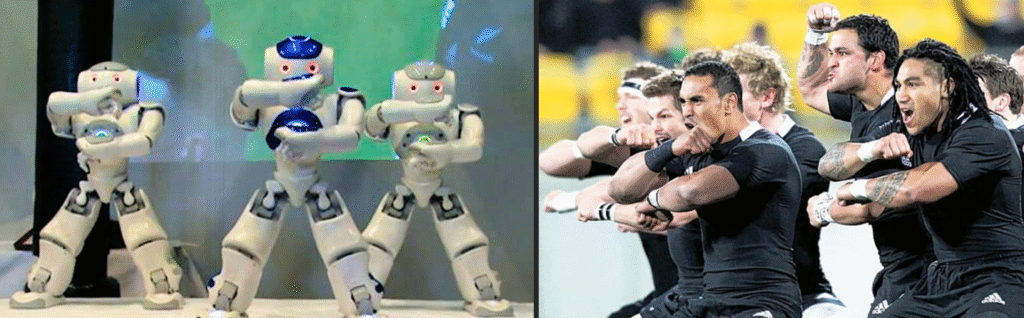

This is what makes the intangible—music, song, live theater, peaceful protest, and rituals like haka—a powerful catalyst for cultural resistance. It’s what made jazz musicians, much like Māori performers, more discerning than their ready-to-entertain audiences in the Roaring Twenties. The intangible factor is in fact so foundational to culturally charged performance that McArthur Mingon, Associate Lecturer at WSU, argues that “robots can’t haka” because Indigenous movement practices require “genuinely embodied knowledge”.

(L) Robots perform the haka in Christchurch, NZ, 2016 (R) All Blacks performing haka | Source: NZ Herald

In a fascinating paper, co-authored with John Sutton in 2021, he notes:

“Skilled performance of haka is deeply mindful, embodying and transmitting dynamic, culturally shared understandings of the natural and social world. The indigenous psychologies incorporated in haka performance are animated by a shared history integrated with its environment.”

This will no doubt become a matter of grave importance as AI humanoid robots eventually learn to emulate sophisticated human behavior with the remarkable outward precision of Diderot’s “trained actor”—where the emotions conveyed, convincing as they are, are not felt as such by the actor.

When you come to see the haka as something more than a “war dance”—as a form of history that is characteristically “breathing”—then you realize how frequently it’s misrepresented in the news and media as a spectacle, a form of entertainment or an intimidation tactic, rather than a form of “embodied history” passed down, quite literally, from human to human.

Misrepresentation and memory

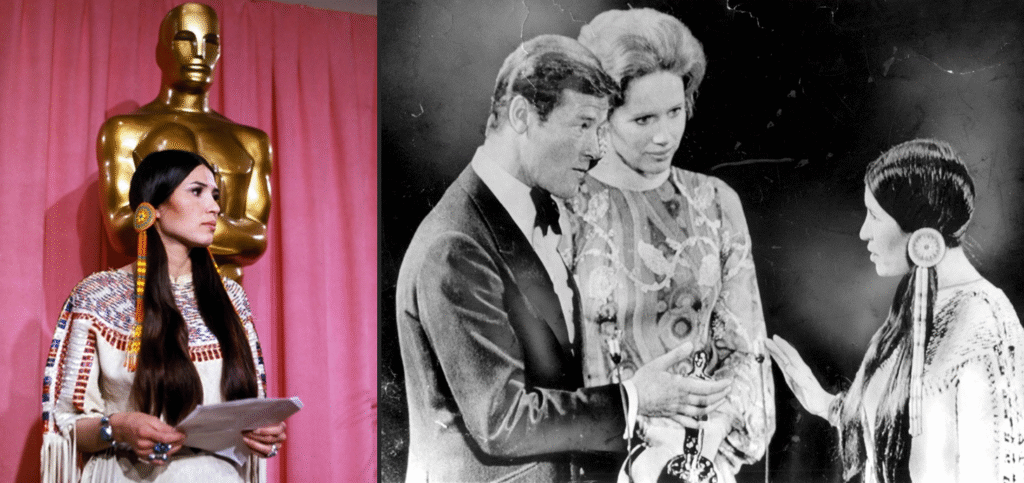

Sacheen Littlefeather declining the Academy Award on behalf of actor Marlon Brando, 1973 | Source: Shutterstock

It’s no surprise that oral narratives built around cultural “truth-telling” have shaped political activism around the world. One particular example comes from the seventies when Native American activist Sacheen Littlefeather appeared at the 1973 Academy Awards ceremony on behalf of actor Marlon Brando. Brando was awarded best actor for his work in The Godfather, which he refused in protest of the misrepresentation and mistreatment of Native Americans in the film industry.

To support the American Indian Movement and their two-month occupation of the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee massacre, 26-year-old Sacheen Littlefeather agreed to share Brando’s statement with the press, but was abruptly escorted off stage after being met with a conflicting wave of boos and applause for her actions.

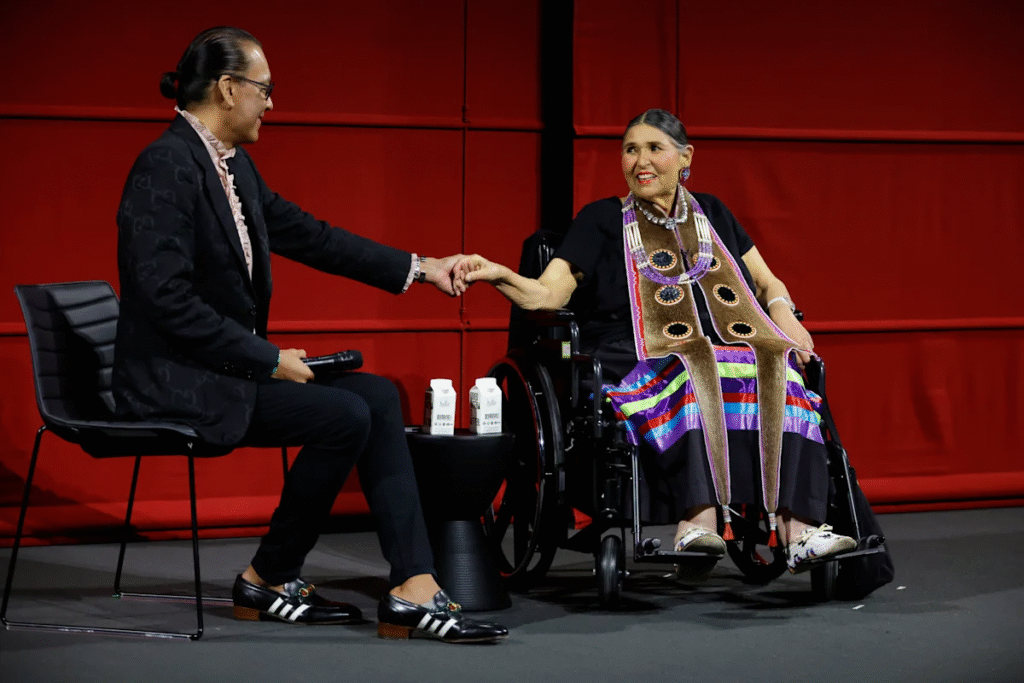

In 2022, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences issued a formal apology and offered a statement of reconciliation to Littlefeather for the “abuse” she endured, calling it “unwarranted and unjustified”. In response, Littlefeather, 75 at the time, accepted the apology just weeks before passing away, touching on the patience of Native Americans. She also agreed to recite Brando’s full statement after being denied the honor fifty years ago.

Bird Runningwater, co-chair of the Academy’s Indigenous Alliance with Sacheen Littlefeather, Sept. 17, 2022 (Source: AMPAS)

Similar attitudes toward peaceful resistance and reconciliation can be found within the world of art, such as the performers, musicians and writers who spearheaded the Harlem Renaissance—which in turn set the stage for the Civil Rights Movement in America. It’s worth noting that the breathtaking improvisation we see today in some of the greatest live performances, from theater and music to political life and sport, comes directly from the longstanding tradition of oral storytelling, where the “unforeseen” becomes greater than any insular ideas set down in stone by a totalitarian Author-God.

This is why the intersection of art and politics matters—and why it threatens the status quo.

“I want to shake people up so bad that when they leave a nightclub where I’ve performed, I want them to be in pieces.” Nina Simone (Source)

It’s also how writer and poet Langston Hughes introduced improvisational technique to his own literary works, most notably in Ask Your Mama, where poetry was written with “room for spontaneous jazz improvisation.” Much of his work influenced Martin Luther King Jr., who evoked his poems in many of his own speeches.

By normalizing oral narratives, Hughes compelled the audience to treat poetry as an ongoing event prone to repetition and revision, constantly re-appearing across time to enable Black performers to testify their experience. Unlike the European tradition of solo conductor-led orchestral playing, the musical arrangement of improvised jazz and spirituals led to intimate and inclusive dialogue between different constituents of the band. This is how instrumentalists grew to “play off of” each other, evoking a communal experience reminiscent of African folk spirituals.

Jazz maestro Duke Ellington performing with other musicians during the Harlem Renaissance | Source: The Collector

Although jazz improvisation quickly rose to prominence, it too faced economic and institutional challenges due to its liminal status as “oral narrative” that wasn’t always recorded or set down.

While legal loopholes around copyright laws for improvised music allowed bebop musicians to play contrafacts without having to pay exorbitant sums in royalties, they tragically deprived them of royalty-based compensation for their own original contributions to music. This is yet another example of the “Western logic of the archive” whereby intellectual property was defined purely in eurocentric terms—reducing memory to a material object in order to control other forms of knowledge. Is it pure coincidence that the same political device is used today to control both artists and change-makers?

Haka as oral history

Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke performing the haka | Source: Getty

We see similar tensions around oral history and performance playing out currently in New Zealand. Last year, ACT party leader David Seymour proposed a bill to radically redefine the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand’s founding treaty with the Māori people, which would have limited their rights. During the vote, New Zealand’s youngest Member of Parliament, then 22-year-old Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke (from the Te Pati Māori party), tore up a copy of the bill and led the Ka Mate haka in a now-viral moment that racked up millions of views.

The proposed bill, which was deemed wildly unpopular (11 to 112 votes in the second reading), has since been rejected. But the haka, which sparked international attention, triggered an ongoing debate about “how to punish” Maipi-Clarke and two more members of the Te Pāti Māori party for their actions that day. In what is now the harshest punishment ever in the history of New Zealand parliament, the privileges committee has recommended a one-week suspension for Maipi-Clarke, and three weeks for two other Te Pāti Māori MPs—which would mean a pay cut and absence from the all-important budget week.

In New Zealand’s 173-year parliamentary history, no member has been suspended for more than three days.

Last year, more than 300,000 submissions were made against the bill that could have redefined the Treaty of Waitangi, and tens of thousands took to the streets to protest the bill outside parliament, speaking truth to power. The Te Pāti Māori party has described the penalty as a reinforcement of “institutional racism” while Labour party leader Chris Hipkins has deemed it “a stain on the House,” remarking:

“Imposing a penalty that removes three members of the House during Budget week—preventing them participating in one of the two occasions the Opposition has in a year to vote no confidence in the Government—is simply wrong. This is not a tinpot dictatorship or a banana republic. We should stand up for the values of democracy, even when they are inconvenient and even when people are saying things that we disagree with. That is not what the Government are doing today.”

In an even stranger twist, the privileges committee took issue with one Te Pāti Māori MP’s wiri gesture, calling it offensive and accusing her of “simulating firing a gun at another member of Parliament” during the haka. Fucking ironic when you consider the history of “the gun” and its historical use against Indigenous people. Talk about gaslighting.

While the debate around “punishment” was delayed until June, the recommendation itself reflects antagonistic attitudes toward Māori culture, evident in their description of the haka as “intimidating members of the house”. For others, like Labour leader Hipkins, the haka was confrontational, but so was the bill. The situation ultimately found its way into sport when rugby player TJ Perenara led a haka for the All Blacks, adding:

“Toitū te mana o te whenua,

toitū te mana motuhake,

toitū te tiriti o Waitangi.”

“Forever the strength of the land,

forever the strength of independence,

forever the Treaty of Waitangi.”

“Haka is something I grew up with, and Haka is something that is gifted from Maori to a lot of New Zealand, and we use Haka in a lot of different realms and a lot of different places. But ultimately, Haka is Maori, and for us to be able to to use Haka in that way, and again, people will try to say that it was divisive, but for us and for the way that we use Haka tonight, was to unify us.” Perenara, 2024 (Source: Rugbypass)

The hero's calling

For some, sports isn’t “the right place” to advocate for causes or make political statements. Sure, but it really depends on the statement, right? Some think the parliament isn’t “the right place” for the haka. Who gets to decide what is and is not appropriate? To put things in perspective, this is the filth circulating on the internet, shaping public perceptions about the haka and Maori culture outside of New Zealand. It’s no surprise that foreign nations end up playing a key role in perpetuating ignorance and penetrating local politics.

Source: Māori EXPLAINS HAKA in PARLIAMENT Debunking Haka is CRINGE | Hapi 117 (YouTube)

In countries where racial and ethnic groups continue to face discrimination, accompanied by grotesque misrepresentations in the media, which are then amplified by social media influencers pocketed by greedy politicians and corporate fat cats, sometimes sport becomes the only remaining place for hope and heroism.

We don’t seem to mind when athletes are clothed in emblems for grubby advertisers. But the moment there’s a hint of what the game really represents to many players and fans, something shifts. The same is true when the “reality” of a player reveals something scandalous. It kills our belief in the game. This is why players draw strength not from the joy of defeating the enemy, but from a history of resilience, and the memory of all the sacrifice leading up to their big moment.

Suddenly the athlete breaks the fourth wall and we realize they are more than avatars playing out a fantasy. A hero is born, fighting a real battle.

Image source: Reddit

Take Makazole Mapimpi. In 2019, he became the first South African to score a try at the 66th-minute in the 2019 Rugby World Cup, helping South Africa win. After scoring the try, he revealed a wristband reading ‘Nene RIP’ in memory of Uyinene Mrwetyana, a 19-year-old woman who was brutally murdered in a post office in Cape Town. The gesture sparked hope in a dark moment for South Africa during the height of gender-based violence. Looking back at the moment, he commented:

“I was doing it for myself, I wasn’t doing it for anyone. It came from my heart because I know the feeling of what it is like to lose someone you love.”

Makazole Mapimpi, Chasing the Sun

Whether in sport or in life, it is memory that drives us forward. It’s why rituals of remembrance matter, not only in sport and art, but equally in politics and everyday life. In some cultures, ancestral calling is strongly linked to identity-formation as it becomes “a life-transforming and therapeutic experience,” key to self-realization. At the end of the day, no one becomes a hero by accident. It all begins with an unlikely invitation to do something you’ve never done before. The question is, do you accept your calling?

“It took many years of vomiting up all the filth I’d been taught about myself and half-believed before I was able to walk on the earth as though I had a right to be here.”

James Baldwin

Thanks for reading my 3-part series on The Theater of Sport: A Hero’s Journey!

🎬 Cool stuff referenced in this piece: All Blacks on Haka (YouTube), Emotional wedding Haka from Euronews, Michael Jordan: The Life by Roland Lazenby, Sonny Boy by Al Pacino, Why Robots Can’t Haka by McArthur Mingon and John Sutton, Sinnerman by Nina Simone, Ask Your Mama by Langston Hughes, Chasing the Sun 1 and 2 (a SuperSport documentary), The Mapimpi Story, Performing Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment by Rebecca Schneider. Enjoy!

💭 Leave a comment!