How Do You Act When You're Angry? (PART 2)

Is anger really as deadly as they say? 😡

Table of Contents

In Part 1, I talked about the toxic outcomes of being aggressively angry in an effort to survive. But what if you’re repulsed by those kinds of personalities—and more likely to withdraw completely?

One of the reasons I had such a hard time recalling an angry moment from my own childhood is ’cause I didn’t do what “angry kids” are supposed to do, like talk back or break rules. I was looking for signs of aggression, when I all I ever did was bottle it up. I’ll be the first to admit how equally unhealthy this can be…

Anger and rage

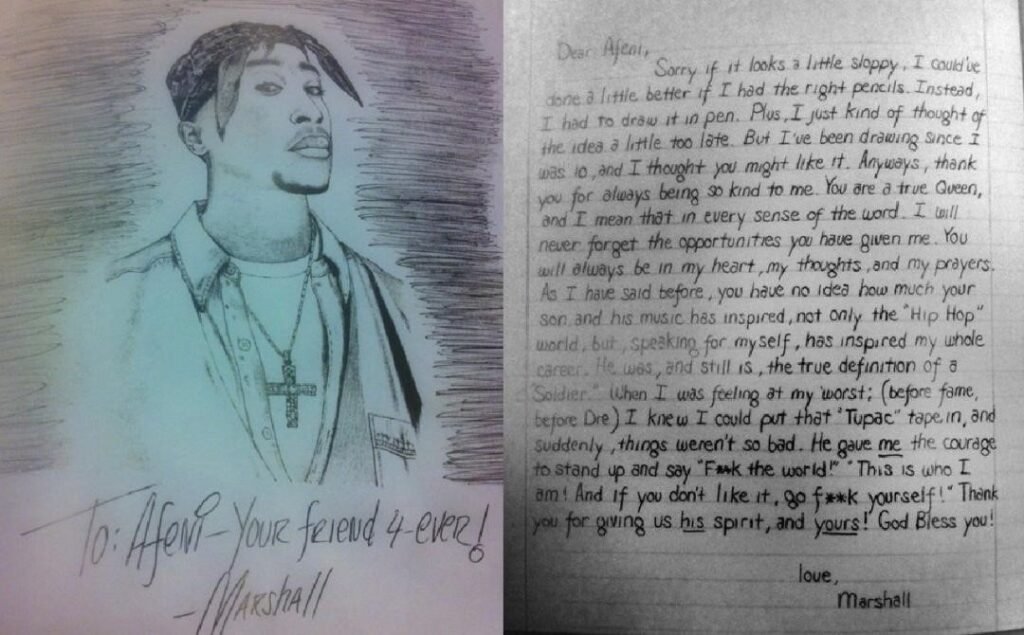

“I’m not gonna lie. There is something inside me that is a little more…happy when I’m angry. It’s like, as bad as it feels to be there, there’s also something about it. There’s a rush of it that I like because it inspires me to say something back.”

Eminem, The Kamikaze Interview with Sway (Part 1)

In one of my older posts on loneliness, I mentioned an interview with physician, trauma expert, and author of When The Body Says No, Dr. Gabor Maté, who shared his story about being abandoned as an infant and how he still felt the emotional scar in his seventies. In the same conversation with Tim Ferriss, he explained the difference between healthy and unhealthy anger, as well as the dangers of suppressing both kinds:

While punching a pillow redirects that aggression, it doesn’t get to the heart of the issue… That’s why we relate so strongly to artists who were once outsiders — just like us. People who process their pain through their art and invite us to be a part of that experience. And it’s no surprise some of the greatest artists express their rage and turmoil by adopting a persona that allows them to say and do all the things we wish we could. The author dies so we may live.

Through art, we’re able to converse with our own pain and hurt in a way that transcends the individual and reveals something profound about the human condition. As Eminem once explained in a 2002 interview about his own persona that’s often inspired and terrified society in equal measure:

“Eminem is the rapper. Slim Shady will kill you. And Marshall Mathers is the person behind the whole, y’know, mask or whatever. That’s the way I see it.”

Additionally, therapy is full of cognitive exercises and techniques that can help us process our rage without necessarily acting out on it. In a sense, the goal of therapy then isn’t learning how to kill the rage, but learning how to nurture the child who had to suppress it. The way Dr. Maté sees it: “Children don’t get traumatized because they get hurt. They get traumatized because they’re alone with that hurt.”

Psychologists frequently talk about emotional trauma, how it gets stored in the body — and how intentional movement or somatic therapy can be a way to feel “safety” through the body. For some folks, martial arts can be helpful in navigating these emotions through discipline, training, and mindfulness. So can yoga, tai chi, dance, and belly breathing due to their emphasis on the same mind-body connection. But there are many ways to process pain, and what works for some might not work for others.

So what happens when anger shows up in a totally different arena, such as sports?

Anger and sports

In Part 1, I talked about the dangers of placing someone with low emotional intelligence in charge of a team, company, or nation. Nowhere is this more evident than the world of sports.

Unlike a field commander who can lead the troops on the battlefield, the coach must watch from the sidelines, huffing and puffing as the players try to execute strategy with precision and skill. You’ve probably heard the phrase “keep your head in the game”. Well, this game is highly emotional. How can it not be? Your family watching from the stands as you sing the national anthem, months and months of grueling physical practice, the stadium so loud and electric you can barely hear your own voice. There’s no way you can keep emotions out of this moment.

That’s why some of the most consistently strong athletes master emotional discipline and learn how to regulate their emotions instead of internalizing or suppressing them. This isn’t the time to feel nothing, it’s time to face the dragon—which is why emotional training matters as much as physical training.

The coach has the high-stakes job of revving up this psychological engine when needed, both on the individual and collective level. This in itself demands acute emotional intelligence and deep psychological insight—knowing when and how to push those buttons without breaching the player’s trust or creating hostility within the team.

There’s no place for unhealthy anger in sports—the raging forest fire that burns everything down with it. But sometimes it is the right place to light a torch in the dark, a flame bright enough to see where you are, and small enough not to singe anyone or anything around it. Context matters, along with trust. In fact, this 2022 study found that instances where coaches expressed low to medium-intensity anger at the team’s defense led to significant improvement in their performance.

In another study, focused specifically on rugby, anger was described as being either “functional” or “dysfunctional”. The former’s the kind that activates a fight-or-flight response and in turn encourages the athlete to confront their situation, while the latter’s the aggressive and retaliatory kind that results in a penalty. Treading that fine line is the coach’s real test, especially knowing that players are already knee-deep in this emotionally flammable quicksand, trying to resist all kinds of deep psychological shit that can come up and weigh them down.

On top of this, when you’re playing rugby for a country like South Africa, you’re not just confronting your physical and emotional limitations. You’re confronting political history, social demons, psychic trauma, promises to yourself and to the people back home. Anger is just one ingredient in this ancient mind-body carnage that predates you. Which is why it takes a certain kind of resilience and tenacity to not only fight in those circumstances, but do so in a healthy way.

This is what rugby players mean by being a warrior—and it’s how the country scored its first ever try in a Rugby World Cup final. By a player who came from “the most hopeless situation in the history of Springbok rugby”.

Since “dysfunctional anger” is an impediment to high performance, it’s imperative that both coaches and players exercise strong self-awareness and emotional strength in order to do their best work. This is where mental resilience comes into play—the kind we also see, perhaps even more so, in single-player sports like tennis and chess.

But what if sports isn’t your thing and you don’t really have any hobbies and you don’t really believe in therapy or just can’t fucking afford it? What then? Does it mean your friends, coworkers, family, and (god help us) your partner, are all stuck with a “you” that’s always on the precipice of an explosion?

How does your unresolved anger affect the ones you love—and those you don’t?

Rage against the machine

No one likes being told what to do, especially if it comes from sociopathic institutions and self-serving authority figures. In fact, sometimes we’re so put off by the suggestion of being told what to do that we go out of our way to do the exact opposite.

This is called psychological reactance and it’s our brain’s resistance to anything that threatens our sense of agency and freedom, consequently resulting in anger, panic, annoyance and, of course, rebellion. I tell you to color within the lines, you color outside the lines. You tell me to speak softly, I speak even louder. I tell you not to subscribe to my newsletter, you subscribe, share, comment, and tell your entire social network to sign the fuck up. See how I like it.

But we don’t break the rules for the sake of it. Sometimes we do it because we feel like someone’s trying to control us. Pulling the wool over our eyes. You might resist a political narrative because you don’t trust the person perpetuating it. Worm-tongued rhetoric laced with false promises. Shameless hypocrisy that breeds societies “rank and gross in nature.” Passive aggressive bullshit.

That’s why films like The Matrix and Fight Club are still so relevant today.

It’s easy to identify with the protagonist, this miserable loner floating through life. While it’s easy to shit on a society that doesn’t seem to care about you, it becomes painfully obvious that you’ve got to wake up and take control of your own life—or it’ll take control of you. In Fight Club, for instance, Tyler Durden is a representation of everything that can go wrong when you take a backseat to your own story. It’s the result of extreme chronic stress from a life you hate so much, you’d rather let a Shadow live it for you.

This may be “Jack’s smirking revenge” but more importantly, it’s “Jack’s broken heart”.

Here’s an alter-ego who’s basically a walking contradiction. “The things you own end up owning you.” Er, right…soooo why are you in Gucci loafers, again?

That’s what makes the film brilliant. Like all good storytelling, it leaves it to us to piece it all together. The unreliable narrator reflects our own propensity for self-delusion. Which is why it’s so fucking ironic that after all these years, the film somehow found an audience in far-right circles, among the Andrew Tates of the world. Here’s what director David Fincher said in a 2023 interview about a new generation of males who have come to idolize Tyler Durden (played by Brad Pitt):

“It’s impossible for me to imagine that people don’t understand that Tyler Durden is a negative influence. People who can’t understand that, I don’t know how to respond and I don’t know how to help them.”

It’s true, we only see what we want to see—and it’s a reflection of the kind of world we’re living in now, one steeped in isolation, narcissism, and stupidity, made more dangerous by misinformation, voyeurism, doomscrolling, and undiagnosed mental illness. But it doesn’t have to be this way. You can still stand up to institutional bullies. You can still say, “Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me!” without jumping from one cult to another. To corrupt politicians. To greedy corporations. To beta billionaires incarnating Jack’s inflamed sense of rejection.

Revenge and balance

“I see the ground is the symbol for the poor people; the poor people is gonna open up this whole world and swallow up the rich people, ’cause the rich people gonna be so fat, they gonna be so appetizing, you know what I’m saying, wealthy, appetizing. The poor gonna be so poor and hungry, you know what I’m saying? It’s gonna be like — there might be some cannibalism out this motherfucker. They might eat the rich.”

Tupac Shakur

Now, of course, I don’t condone violence. Do you? No really, do you? Yeah, I didn’t think so.

Come to think of it, I don’t know anyone else who does either. Yet for a society that’s supposedly repulsed by blood, gore, and “crimes of passion,” we sure get off on it. Just look at the movies and top trending shows on TV. True crime, murder mysteries, revenge narratives, war stories, good guy gone bad. Guts, fingers, ears, brains splattered across those 1950s-bathroom tiles in broad daylight. Dismembered bodies sprawled across some rich jerkoff’s pristine white sofa. Why? Who? What? When? We want to know it all, every gruesome detail. Of course, we don’t condone it. Oh, god, no. We’re just…curious. Frustrated. Enraged. Stimulated. It’s not like we did anything. We just want to know why and watching isn’t doing…is it?

But why do we do it? Why do we need to watch things die from a distance?

This is where someone goes on a tone-deaf tirade about the dangers of violent media, video games, songs about guns, death, murder, and Tarantino’s entire filmography. These are probably the same people who believe there’s a time and place to “enjoy” obscenities. But even so, where would that leave us with warfare, police brutality, legalized torture, and a broken healthcare system designed to keep big pharma alive?

Divorcing violence from reality would mean glossing over a significant part of human nature. It would preclude us from studying history, politics, literature, art, from understanding the basic tenets of culture and society and the very notion of crime and punishment—absurd and arbitrary as it may seem sometimes.

How else would you explain slavery? Colonialism? The French Revolution? Apartheid? Police brutality? The Holocaust? The Civil Rights Movement? Bob Marley? Hamlet? Rock music? Folk music? Hip hop? War and peace? Tom and Jerry?

Violence isn’t the work of the devil; it’s a product of biology. It’s how you come into this world—covered in blood, guts, and feces all around you. It’s also why horror—as we experience it in film, music, and art—can be a powerful release for an internal rage we can’t even begin to comprehend. As Thessaly La Force observes in this terrific piece on rage and horror, specifically in the award-winning film Parasite:

“On the one hand, it’s surprising that these East Asian societies that so value obedience should have perfected the revenge narrative in popular culture, though on the other, it isn’t at all: When the idea of obedience is used to justify authoritarian governments and socially rigid hierarchies, rebellion is never far-off. […] Rage is a destructive emotion in this equation, but within art, it is also radical and, in rare moments, elucidating. The best of these films understand that the outcome of pitting people against one another can be violent, that it will invariably end badly. But they also understand that a repressive society can transform individuals into monsters.”

Instead of waving our finger at these so-called “random acts of violence,” maybe it’s time we looked at all the contradictions within ourselves and the society we live in.

(Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, 1964)

After all, one of the biggest reasons people turn to revenge stories in the first place—be it video games or movies or music—is the sense of control it gives back to an otherwise powerless “free agent”. As David Chester, head of the Social Psychology and Neuroscience Lab at Virginia Commonwealth University notes:

“Aggression isn’t just about ‘I’m angry and I want to hit someone.’ It’s also about how it feels good sometimes to get revenge on someone who has wronged you or who you perceive as having wronged you.”

Anger and justice

“Even when you earn, you owe.”

An interesting way to determine if the general public “feels wronged” is to see if they switch sides during a major election. If people want change, sure, they might protest…but more often than not, they’ll turn their back on a party that they feel has turned its backs on them. It’s not a pragmatic decision; it’s an emotional decision. You’re driven by fear and — you guessed it — anger.

It’s the same reason why people leave high-paying “dream jobs” after watching megalomaniacs rise to power in an organization they once venerated. The same reason right- or left-leaning public figures suddenly switch to the other side after feeling bullied or coerced into changing their opinion. The same reason most candidates use “other-ing” tactics to improve their rankings.

It’s why we see “They not like us” messaging in every goddamn political campaign these days. (Cringe warning).

Sure, sometimes this comes with the territory. If someone’s running for office, they’ve got to show what they’ll do that the last asshole didn’t. But often, it’s the same ol’ bullshit to get you to swing in their direction. When the majority is poor and overworked, it’s so much easier to create a public enemy we can collectively shit on for all our problems. Immigrants. Conspiracy theories. Foreign nations. Dead presidents. Hate becomes a powerful instrument for control and persuasion, especially when you’re already frustrated with the world. It’s the oldest trick in the book. Divide and conquer.

But we fall for it. And now you do what they toldja.

But if you had 24 hours to live, would you still be thinking about all the things you hate, or all the things you could have done but didn’t because you were too busy hating the absolute piss out of everyone who didn’t look and sound like you? It’s too bad we fear what we don’t understand.

That’s the premise of The 25th Hour, the first major film that dealt with New York City in the aftermath of 9/11. It follows Monty, played by Edward Norton, whose life is basically over and he realizes how much time he’s wasted blaming the world for everything—culminating in this famous vitriolic rant. Here’s how Norton summed up the real tragedy: “To me it’s a story about the consequences of not examining the morality of what you’re doing.”

It’s the same theme that plays out in the painful but necessary story of American History X, a 1998 film—also starring Norton—that shows us how hate gets politicized and passed down from generation to generation. I must admit, this is the only film I was reluctant to revisit because I remember being so utterly distraught when I first saw it. And yet, it’s never been more relevant in our increasingly polarized society.

What I’m getting at is violence is indeed part of human biology. But when violence meets hate, it’s symptomatic of a much larger, more elaborate and multifaced problem that’s also societal, systemic, psychological, and POLITICAL in nature.

- Hate requires the creation of an “in-group” and “out-group.” A clearly defined and socially identifiable “Us” and “Them.” White vs Black. American vs Asian. Right-wing vs left-wing.

- Hate speech is often used to establish in-group solidarity and sometimes even an attempt to fill a void, which is why chronic loneliness coupled with disempowerment often leads to violence and aggression.

- Hate requires us to dehumanize the out-group aka “the other” and deny their personhood entirely in order to derive pleasure from their pain and suffering. This is an extremely common tactic used in warfare—and it’s how torture becomes institutionalized.

Moreover, while hate can be taught, reinforced, and sometimes even embedded in some of our so-called values, it’s also neurologically visceral in nature. Stanford neuroscientist and author of Behave: The Biology of People At Our Best and Worst, Dr. Robert Sapolsky explains:

“People are very rarely reaching their hatreds out of some sort of rationality. They’re reaching their hatreds out of fear and out of displacement than that of the history of their own suffering and all of that. And it is visceral and it is emotional. There are, you know, hundreds of milliseconds before your conscious rational cortex begins the job of figuring out why that visceral hatred actually makes perfect sense. And that fits perfectly with these pictures of authoritarianism—and why it’s so easy to make people like that decide that those “Thems” are vermin and rodents and malignancies and feces.”

Throw in biased media, political theater and massive wealth inequality into this authoritarian rhetoric and you’re looking at less rational decision-making and more emotionally-driven behavior that’s engineered to make the rich richer and the poor poorer. And we’re not just talking rich. We’re talking about the 1% that owns half the world’s wealth. That’s some Squid Game shit right there.

Bottom-line: Human behavior is complicated, but “divide and conquer” tactics are not. They rely on our tendency to act out of fear, hate, and anger rather than reason.

That’s why we need more varied and nuanced conversations—more perspectives that make us think and question, that remind us of our humanity, that we’re all going through the same shit. And that maybe, we’re not as different as some would have us believe… especially when the political climate starts making us sweat in the dead of winter.

👋 Hey, you hot-blooded hopeful!

➡️ CHECK OUT PART 1 where I discuss anger in childhood and bullies in politics.

🎬 Cool stuff referenced in this piece: “The Way I Am” by Eminem, The Matrix by the Wachowskis, “Passive” by A Perfect Circle, Chasing the Sun 2, a sports documentary by James Cook, Greg Lomas, and Gareth Whittaker, Interview with Tupac Shakur sampled in “Mortal Man” by Kendrick Lamar, Fight Club by David Fincher, “Killing in the Name of” by Rage against the Machine, “Vicarious” by TOOL, Django Unchained by Quentin Tarantino, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb by Stanley Kubrick, “Not Like Us” by Kendrick Lamar, The 25th Hour by Spike Lee, American History X by Tony Kaye, and Do The Right Thing by Spike Lee. Enjoy!

💭 So whatcha think? How are you coping with all the anger simmering in society and life in general? Let me know in the comments below!

💜 Thank you for supporting my content. If you like what your read, subscribe to my newsletter to get notified when my next post is live!