Searching for Authenticity

Exploring the in-betweenness of being human.

Table of Contents

Can you talk to yourself in the mirror without feeling like a phony? Give yourself a pep talk when things are falling apart? Like you were your own friend. Your own coach. “Life’s a game of inches” and all that.

Feels like one of those try-not-to-cringe challenges, doesn’t it?

It’s serious business when Al Pacino gets into character, but something out of SNL when we give it a go. Maybe you don’t have the acting chops to transform into Scarface. But I bet you know how to shapeshift into a different version of “you”. We all do.

We suspend our disbelief and rehearse for life’s big moments. An interview, a retort, a proposal—hell, I’ve rehearsed small talk to prevent awkward silences (with moderate success).

The waiter asks the same question as they hand you the bill. Colleagues compliment your raggedy outfit when they need something. You pretend to be asleep to avoid tough conversations with your partner. It goes on and on and on.

We’re all guilty of enabling bad performances, applauding each other’s half-assed attempt at sincerity. But every now and then, we take our role more seriously.

We dress up mindfully for a formal event, and dress down carefully for a casual one. We rehearse talking points for a corporate dinner and funny anecdotes for parties. No matter the role, we’re constantly concealing the amount of effort it takes to play it smoothly. As if revealing the behind-the-scenes work would make the act less “sincere”. So we become illusionists, performing tricks for an audience desperate for magic.

Audience infidelity

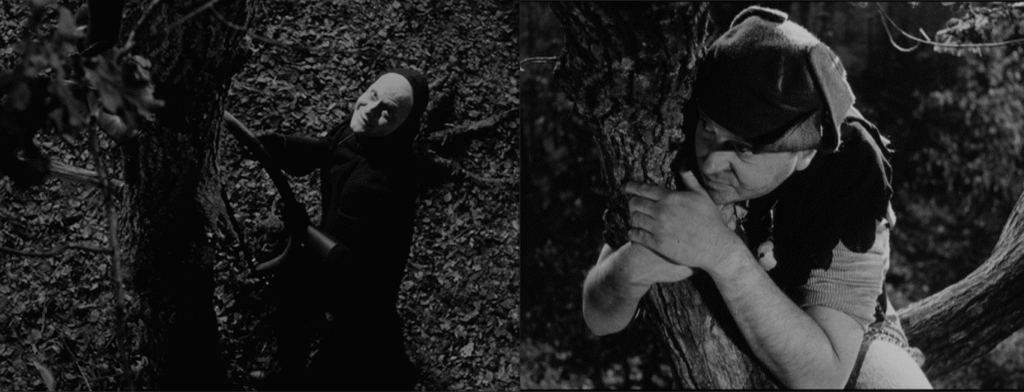

(The Seventh Seal, 1957)

“I’m cutting down your tree because your time is up.”

“But I have a performance!”

“Cancelled on account of death.”

We tend to think real acting only happens on stage or films sets. But when we’re living the mundane—ordering at a restaurant, speaking in a work meeting, waiting in queue, going on a date—we’re all trapped in the awkward, contrived machinations of a performance we can’t escape.

To some degree, we need a mask to participate in the drama of life. Family encourages it. Work demands it. Society imposes it. In life, as on stage, acting demands total commitment. Also in life, as on stage, actors are only as good as their script. If you’re not willing to write your own, what else are you willing to gamble?

It’s the kind of thing that makes you mistrust what people say, doubt their intentions, and limit access to your audience. Which is precisely what the author of The Catcher in The Rye did.

“In 1953 Mr. Salinger, who had been living on East 57th Street in Manhattan, fled the literary world altogether and moved to a 90-acre compound on a wooded hillside in Cornish. He seemed to be fulfilling Holden’s desire to build himself “a little cabin somewhere with the dough I made and live there for the rest of my life,” away from “any goddam stupid conversation with anybody.””

The New York Times, “J. D. Salinger, Literary Recluse, Dies at 91” (2010)

Later that year, the fiercely private writer agreed to do an interview with some high school students for their school page, only to discover it published as an editorial feature. “Mr. Salinger felt so betrayed,” writes Charles McGrath, “that he broke off with the teenagers and built a six-and-a-half-foot fence around his property.”

Designing behavior

Wouldn’t it’d be grand if you could perform “sincerely” all the time? Be your unadulterated self without ever offending your audience? But everyone needs a filter. So we become “finnicky by proxy”.

We design our own masks, using whatever materials we can find. Movie characters, superheroes, rockstars, athletes, all stitched into the fabric of puberty and adolescence.

But who do you become when the mask clings too tight? When the corners dig too deep, what then? Do you bleed through the act, or do you break character?

It’s only later in life that we discover design creates behavior. That perhaps we adorn a mask that doesn’t represent us at all. For those who don’t fit into a prescriptive role, “acting” becomes an analogy for life itself. It helps us rewrite our story with the pen of our own imagination. To say and do things with a kind of gleeful abandon really only acceptable in the world of art.

Often, acting illuminates the very thing we repress: that you are at once you and not you, coexisting in this social paradox—where “being” is simply role-play, and society, a place of make-believe. Observing life as theater grants us this sociological sentience—it imbues our mask with meaning, and our actions with intent.

Suddenly we see the social machinery that writes our tragedies. And nothing’s ever the same.

Do you even care?

“I think that’s part of what’s real and what’s not real. Who’s the architect and the director of the material?”

Keanu Reeves, The Verge (2022)

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, we seem to be living in a never-ending period of transition. Somewhere between social distancing and forgetting to turn our mics off, we turned “stuck-in-limbo” into a statement, an attitude, a mark of resilience.

On one hand, this “in-betweenness” offers a much-needed break from redundancy. It creates fluidity, a sense of curiosity and play. Something’s changed in the theater of life—and it’s forcing us to rewrite our script. On the other, it’s also a period of immense confusion, disorientation, and chaos. Stretched too long, it can lead to new forms of “being” marked by chronic anxiety, purposelessness, or worse, total oblivion.

For writer Dan Sinker, some of us have already caved. “It’s so emblematic of the moment we’re in, the Who Cares Era, where completely disposable things are shoddily produced for people to mostly ignore.” He goes on to share his experience working on a cool project about the metaverse with a big-budget studio, which ultimately fizzled, in short, because no one cared:

“Over the course of two months, we went from something smart that would demand a listener’s attention in a way that was challenging and new to something that sounded like every other thing: some dude talking to some other dude about apps that some third dude would half-listen-to at 2x speed while texting a fourth dude about plans for later.”

Sinker’s experience echoes a bleak reality similarly conveyed by actor Keanu Reeves three years ago. In an interview with The Verge, Reeves talks about a time he had dinner with a director and his teenage kids who hadn’t seen The Matrix. When asked to summarize the plot, he got stumped mid-conversation by their reaction:

“So I’m starting to say, “Well, there’s this guy who’s in a kind of virtual world, and he finds out that there’s a real world, and he’s really questioning what’s real and not real, and he really wants to know what’s real.” And the young girl was like, “Why?” And I was like, “What do you mean?” She was like, “Who cares if it’s real?” and I was like, “What? You don’t care if it’s real?” And she was like, “No.””

Keanu Reeves, The Verge, 2022

What kind of dystopian meta-universe are we living in where the guy who played Neo pulls a Morpheus over dinner with a bunch of baby-Cyphers going, “Ignorance is bliss, dude”?

I’ll admit, it’s hard to find the will to create anything personal (and therefore meaningful) for an audience that doesn’t seem to give a shit. But for whatever reason, Sinker remains excited about his project, imploring the reader to pursue their own: “In a moment where machines churn out mediocrity, make something yourself. Make it imperfect. Make it rough. Just make it.”

Simulation anxiety

“Can we just not have metaverse be invented by Facebook? Just the concept of metaverse is, like, way older than that. It’s, like, way older. And so for that moment to get to… I’m just like, come on, man.”

Keanu Reeves, The Verge (2022)

Sinker and Reeves’ stories touch on an important shift in audience consciousness. Half the time we know what we’re watching is somewhat staged, similar to reality television. But we watch it anyway. But maybe it’s not because we’re oblivious to “the truth”. Maybe it’s because hybridity is just more indicative of the times we’re living in post-pandemic—somewhat surreal, somewhat absurd, kind of unstable, and mostly neurotic.

We needed a distraction when we were stuck in the pandemic-elevator. We channeled our neurosis to survive a deadly virus. Industrial-grade masks, incessant handwashing, work-from-home mandates, vaccine obsession. Manic panic was the norm. It served a purpose.

Now, more than five years later, it’s leaked into work, culture, entertainment, news. It’s changed the way we sanitize body and mind. It’s a way of life. Behavior re-designed.

It’s scary to think younger generations may not care for “what’s real”. But every generation has their own god—their own authority on “truth”. What was real to my grandparents thankfully isn’t real to me, and what’s real to you may not be real to your grandkids. Even the best ideas have a shelf-life.

Right now, trust in social institutions has eroded, paranoia is sky-high. We’re drunk on survival mode, dreading the next big catastrophe. It’s cause-and-effect. No vaccine for fear.

Perhaps it is a mad world. Perhaps it’s okay to accept that things aren’t what they appear to be. Maybe that’s why some of us are seeking solitude in that place of in-betweenness—the play within the play that holds a mirror up to society—where jesters make better “truth-tellers”, and businessmen, religion.

Maybe the actor and the audience finally have something in common.

Maybe we’re all just sick of playing the same part.

*****