Are You Sincere or Cynical?

Who’s to say, really?

Hal: Hey, if you can see something and hear it and smell it, what keeps it from being real?

Mauricio: Uh, third-party perspective? Other people agreeing it’s real?

(Shallow Hal, 2001)

Table of Contents

Everyone claims to be obsessed with the truth. We want authenticity. The whole truth and nothing but the truth. But the closer you get to “the whole truth”, the smaller it seems to get.

I don’t know about you, but anytime I’ve been moved by some semblance of “truth”, it always reveals itself in some miniscule detail—a note in a song, a line in a poem, a glance, a step, a whimper. Why does this larger-than-life unifying force appear to us contrarily in fragments? And why do we chase something eternally out of reach? Is it really truth we desire—or a piece of it?

In sociology, we learn time and time again that humans aren’t necessarily concerned with “truth”. In most cases, we can’t handle it and many a Galileo have died making this point. Above all else, we seek control and social order—and we’re willing to give up a lot to maintain it. So we swing back and forth between wide-eyed wonder and total disbelief, between sincerity and cynicism, driven partly by peer pressure and partly self-interest.

Motive opens up artistic choice, not concerned with rightness or wrongness, truth or falsehood, but with an irrepressible need to adapt.

That’s why deconstructing our outlandish behavior requires an outlandish observer. Someone who can see through the whole act—starting with their own.

The sincerity-cynicism spectrum

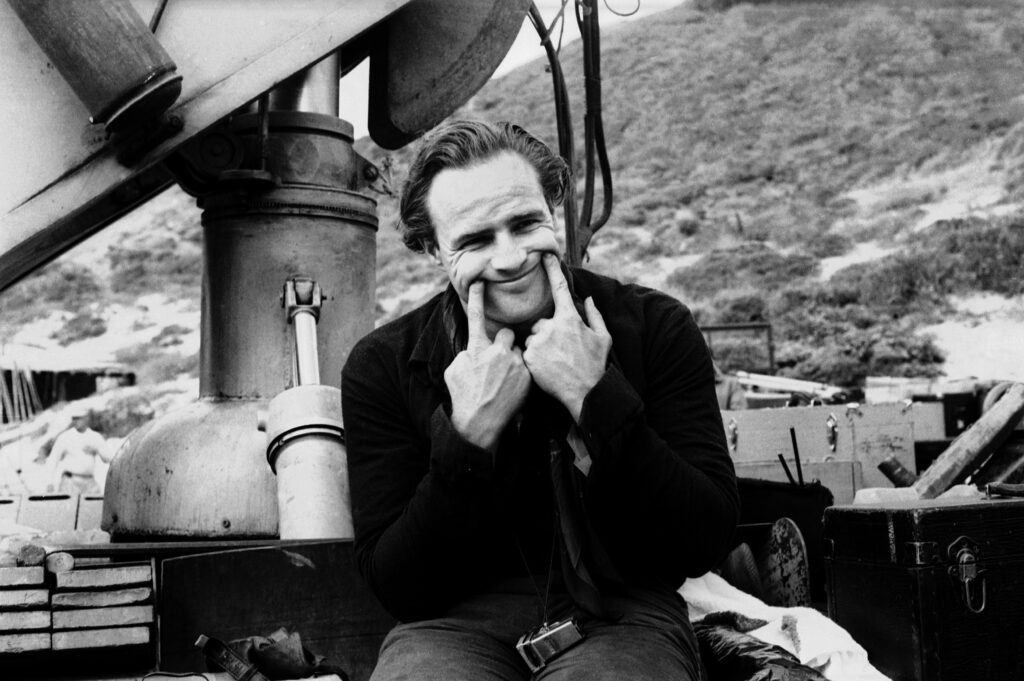

Getty Images

“I was always interested to guess the things that people did not know about themselves.”

Marlon Brando (Listen to Me Marlon)

Anyone who observes human behavior from the perspective of an outsider might conclude, as Marlon Brando famously did, that “life is one big improvisation.”

“I was always somebody who had unquenchable curiosity about people. I would watch people for three seconds as they went by and try to analyze their personalities by just their flick. The face can hide many things and people are always hiding things.”

Marlon Brando, tapes from Listen to Me Marlon (2015)

In his autobiography, Brando further elaborated on his complex relationship with acting as a profession, which he couldn’t entirely separate from how people performed in everyday life. “If I hadn’t been an actor, I’ve often thought I’d have become a con-man and wound up in jail. Or I might have gone crazy,” he wrote in Songs My Mother Taught Me. “Acting afforded me the luxury of being able to spend thousands of dollars on psychoanalysts, most of whom did nothing but convince me that most New York and Beverly Hills psychoanalysts are a little crazy themselves.”

Interestingly, sociologist Erving Goffman also attributed the ability to recognize “the realness” of a moment not to the actor nor the psychoanalyst, but to “the socially disgruntled”. A skilled ethnomethodologist, he observed people in meticulous detail from the outside-in, like an alien note-taking from another planet.

Goffman spent most of his career observing social interactions in social institutions that govern conformity and control, such as prisons, asylums, hospitals, boarding schools, and military barracks, describing people’s oscillation between “sincerity” and “cynicism” more as a matter of necessity than choice:

“An individual may be taken in by his own act or be cynical about it. These extremes are something a little more than just the ends of a continuum. Each provides the individual with a position which has its own particular securities and defences, so there will be a tendency for those who have travelled close to one of these poles to complete the voyage. […] The cycle of disbelief-to-belief can [also] be followed in the other direction, starting with conviction or insecure aspiration and ending in cynicism.”

Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, 1959

Can you stop acting?

“Life trickles in from the outside, and you’re forced to react. No one asks if it is true or false, if you’re genuine or just a sham. Such things matter only in the theater, and hardly there either. I understand why you don’t speak, why you don’t move, why you’ve created a part for yourself out of apathy. I understand. I admire. You should go on with this part until it is played out, until it loses interest for you. Then you can leave it, just as you’ve left your other parts one by one.”

(Persona, 1966)

Sometimes we view the sincerity-cynicism spectrum as a kind of moral compass whereby sincerity equals “good” and cynicism equals “bad”. But this makes no sense when you consider the simple fact that we’re not so much choosing between honesty and deceit as straddling between conformity and deviance—between acceptance and resistance.

If you interpret “sincerity”, as Goffman did, as belief in one’s own act, and “cynicism” as the ability to see through it, then acting becomes less of a moral compass and more of a pendulum, constantly in motion.

It is here, in this liminal space, that anxiety crops up—that awareness of being perpetually in between—that lends itself to performance. “Control over your life begins with this life,” Brando’s acting teacher Stella Adler said of the theater. “It is against the nature of human life to withdraw.”

The deconstruction of acting

Illustrator: H. C. Selous

“There is a kind of confession in your looks, which your modesties have not craft enough to colour.”

Hamlet, Act II, Scene II

As much as we enjoy moralizing a certain “Method” when it comes to acting, we can’t possibly share our deepest, most complex life experiences without traveling along the sincerity-cynicism spectrum. It’s this range that allows us to be at once mutable, discerning, perceptive, and likewise, expressive, reactive, confrontational.

Most of the time, we travel along the spectrum unconsciously, transitioning from one social frame to another. We feel joy watching a 90-year-old couple in love. We cry when a film mirrors a feeling we could never articulate. You don’t have to think, it just happens. That’s an acting technique—one that demands total vulnerability and presence.

But when we seek control, we overthink, separating body and mind. And the mirror can be cruel to a disembodied actor. Often it exposes the very thing we’ve been conditioned to hide: our deepest insecurities, our festering shame, our desperate need for acceptance.

Cynicism is a disruptive acting technique, not because it’s bereft of honesty, but because it demands the involvement of a vulnerable audience, willing to play along. That’s why film theorist Leo Braudy reminds us: “Adults suffer from an etiology of ‘bad acting disease’—and curing this disease is a tall order.”

“You’re tearing me apart!”

L to R: James Dean (Rebel Without A Cause)

Tommy Wiseau (The Room)

James Franco (The Disaster Artist)

And yet, you can’t escape it. Communication, like life, requires reproduction. Reproduction of word, sound, mood, movement. It’s inherently performative. Every time you attempt to tell a story, you reproduce it to capture the full breadth of the experience. Acting, good or bad, sincere or cynical, is the only way out.

In life, as on stage, all performance is art. And all art is memory re-constructing itself.

It’s the ongoing evolution of storytelling, a testimony of the human experience, where every account matters. If we didn’t have James Dean, we wouldn’t have Tommy Wiseau. If we didn’t have Tommy Wiseau, we wouldn’t have “the most wonderfully terrible one hour and thirty-nine minutes ever committed to celluloid” aka The Room. And if we didn’t have The Room, we wouldn’t have the self-reflexive beauty of The Disaster Artist.

What happened behind the scenes of “the greatest bad film ever made” was arguably wilder than the film itself. But it took Greg Sestero’s double consciousness to relay that story. A “sincere” actor who showed up with total commitment, and a “cynical” observer who saw through it. As one of the leading actors in the film, Sestero wrote about the experience in what eventually became a NYT’s bestseller, later an award-winning film.

It all came full-circle… unlike this sublime plot-hole from The Room.

(The Room, Wiseau-Films, 2003)

“I got the results of the test back. I definitely have breast cancer.”

But how did The Room become “the Citizen Kane of awful”? More importantly, how did it amass a fandom? Writer Vince Mancini sat down with Michael Rousselet, one of the film’s “very first viewers“, who contributed to its popularity. Here’s what he was told when he asked for three tickets to see it for the first time.

“This movie’s really bad, guys. Everyone walks out.” And they pointed to an IMDB review, and the review that they had stuck on the window said: This film is like getting stabbed in the head. And I was like, “Now we’ve GOT to see it.”

When I first watched The Room, I cried laughing. When I watched the film adaptation of The Disaster Artist, I caught myself tearing up near the end. Both are a gift. Both capture, through a hysterical “this-really-happened” lens, our deepest, most vulnerable desire to be taken seriously.

Ultimately, what The Room and its fourth-wall-breaking companion offer is a rare message from the audience to the audience: Try zooming out of the absurdity we call life—beyond the politics of “sincerity” and “cynicism”—and you’ll almost always find something to laugh about.

*****