Stress, Storytelling, and Survival: Why We Lie to Ourselves

If you stop noticing your own lies, do you start believing in others'?

Table of Contents

This is Part 4 of a four-part series on Everyday Deception. Check out the rest:

It’s a cold and miserable day in the dead of Canadian winter. Back-to-back meetings made worse by an impending oral exam at the dentist. I’m dragging my feet on my way to the clinic when I hear a faint echo in the background. I turn around to see a teenage girl waving her arms at me as if I’d dropped something. She runs across the street to catch up while I dig into my back-pocket. Wait. I don’t remember carrying anything. Now the closer she gets, the weirder it feels. Is she… okay?

“You’re a special person,” she blurts out, breathless from the sprint. “And I have a message for you.” She abruptly hands me a booklet and takes off without another word…

Okay. This is downtown. I’ve seen weirder. And hey, a little positive affirmation never hurt anyone. Frankly, I could use a little pick-me-up today. A new adventure lies ahead. Great things come to those who wait. Your success will astonish everyone. So let’s hear it… what’s my destiny, booklet?

Alas, no fortune cookies here. Just a “made you look”-moment from the Mormon Church. 🤡

What the hell was that?

I was so perturbed by this kid’s sales pitch that I spent the next hour in the dental chair feeling dumb as a rock. Why did I even entertain her for a second? The whole thing reminded me of my own experience in marketing. Hours of creative brainstorming to convert cold users into warm leads. And that one time I’d been “converted” myself by a pushy donation seeker on a particularly bad day. It all makes you realize how much of our actions are based not on the sale per se, but the stress we’re experiencing during the interaction.

Most of the time we don’t even take action because we care; we do it because we want to feel in control. Leave it to a neurotic to fix the unfixable.

Sure, a good salesperson can probably sell ice to an Eskimo — but not without understanding them first. Think of urgency at checkouts (Hurry! Offer expires in x mins). Emails tapping into your fear of missing out (Your favorite item is selling out fast!). Distracting pop-ups offering freebies in exchange for user loyalty (you get mine in exactly 150 seconds after landing here). The better your understanding of human behavior, the better your chances of creating desire — whether it’s for something real and meaningful or something that doesn’t exist.

Systemic deception

(L) Bernie Madoff | (R) Robert De Niro as Bernie Madoff

Let’s be clear. It’s not the performative aspect of communication that’s to blame here; it’s the indecipherable motivation behind it. After all, a good salesperson is nothing more than an effective communicator. And effective communication is vital for human survival, both in life and business.

Take money, for instance. When we make financial decisions, we often turn to professional advisors and reputable institutions that are legally obligated to serve us. But no matter how careful you are, how extensively you research something, you’re essentially taking a risk. Life is unpredictable. This is complicated by the fact that financial decisions tend to be highly emotional, giving banks, ad agencies, stockbrokers, self-help gurus, charities, and social media influencers the chance to persuade you into taking action.

Incidentally, much of the techniques used by scammers can be applied to reputable institutions that try to warn us against them. Take this article by The Royal Bank of Canada. It lists common tactics used by scammers to help you identify shady behavior: “Creating urgency,” “using scare tactics,” “preying on emotions,” “insisting on secrecy,” “creating believability”. Ironically, many of these tactics can be used describe a financial institution’s own predatory practices. It’s the same playbook.

We’re told to think before we act and conditioned to act before we think.

This is how people on the inside learn how the game is played. No matter how ethical or sincere your cause, every organization has a designated space for research where behavior can be monitored, measured, and manipulated to “legally” drive organizational success — often at the expense of those they claim to be serving.

Team performance

“You schnooks will now be targeting the wealthiest one percent of Americans. I’m talking about whales here. Moby fucking Dicks. And with this script, which is now your new harpoon, I’m gonna teach each and every one of you to be Captain fucking Ahab. / Captain who? / The book, motherfucker! From the book!” (The Wolf of Wall Street, 2013)

If you accept the idea that you can have anything you want if you just worked hard enough, you’re no longer selling a product. You’re selling a lifestyle.

Do you have what it takes? Can you seize the moment?

It’s the kind of drug that makes selling pens and paintball tickets feel like life or death.

We see the allure of this drug, and an assortment of others, in Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street based on the best-selling memoir by former stockbroker-turned-salesman Jordan Belfort who defrauded hundreds of millions from investors. In the film we see the antics that lead to this clusterfuck. Armed with a cold-calling script, Belfort not only manages to train “a bunch of jerk-offs” into selling worthless penny stocks on an insane commission, but eventually succeeds in manipulating the stock market.

But Belfort isn’t just out to make a shit ton of money for himself — he wants to teach his ways and help his accomplices get filthy rich. The whole thing echoes “team performance” the way sociologist Erving Goffman described it in the early ‘60s. In a detailed dramaturgical analysis of team work in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Goffman likens the foundations of a team to that of a “secret society” in the way it helps establish and reinforce group identity:

“A team, then, has something of the character of a secret society. The audience may appreciate, of course, that all the members of the team are held together by a bond no member of the audience shares. However, the individuals who are on the staff of an establishment are not members of a team by virtue of staff status, but only by virtue of the co-operation which they maintain in order to sustain a given definition of the situation. ”

The art of selling

Source: Couch Potato Facebook

This is no different from the loyalty we forge with coworkers in the name of company culture or organizational politics. As with a secret society, normalizing this loyalty requires a fair share of repetition and ritualistic bonding, not the least of which include weekly stand-ups, coffee chats, team-building activities, larger-than-life retreats, and a theatrical display of solidarity formalized by “Kumbaya”-style employee communications. Even though the whole thing is staged to the nth degree, it doesn’t feel as such. Because the more you rehearse something, the more familiar it feels.

But team loyalty isn’t confined to a conventional 9-to-5 job.

We see the same principle at work in organized crime and elaborate scam operations that require trust and cooperation within the hierarchy. Despite competition and rivalries similar to the ones we see at the office, members of a criminal network must find ways to work together like a family. New York Times reporter Selam Gebrekidan notes:

“The matchmakers are essential to the [money laundering] system and their work is so repetitive that the Chinese name for it is ‘moving bricks,’ according to Yanyu Chen, an anthropologist who studies money-laundering schemes in Cambodia.”

Left: The real Jordan Belfort | Right: Leonardo DiCaprio as Jordan Belfort

This is where the leader’s communication and delivery comes into play, acting as reminder of why “the work we do together matters,” similar to the rhetoric of a presidential address… or a charismatic cult-leader. In a 2014 interview, DiCaprio reflected on his own fascination with Jordan Belfort’s real-life speeches to his staff, and how it felt to reenact them for the film:

“I’ve been thinking about these speeches for almost six years and mechanically breaking them down. But it wasn’t really until I was on that stage where it kind of took on a life of its own. I kind of felt closer to what Jordan [Belfort] must have felt during that time period where he almost created a cult for himself… being consumed by that adoration and the power of, you know, being able to provide wealth to this mass of people that were worshipping him. When I got on that stage, it kind of took on this incredible life of its own and I felt like I was… Bono or some rockstar… even though I knew that these actors were paid to clap every single time I was shouting at them! You get this incessant need to push them forward. And it almost became like this Braveheart speech—or cry for battle—except it was persuading them to go out there and, you know, essentially screw as many people over as possible.”

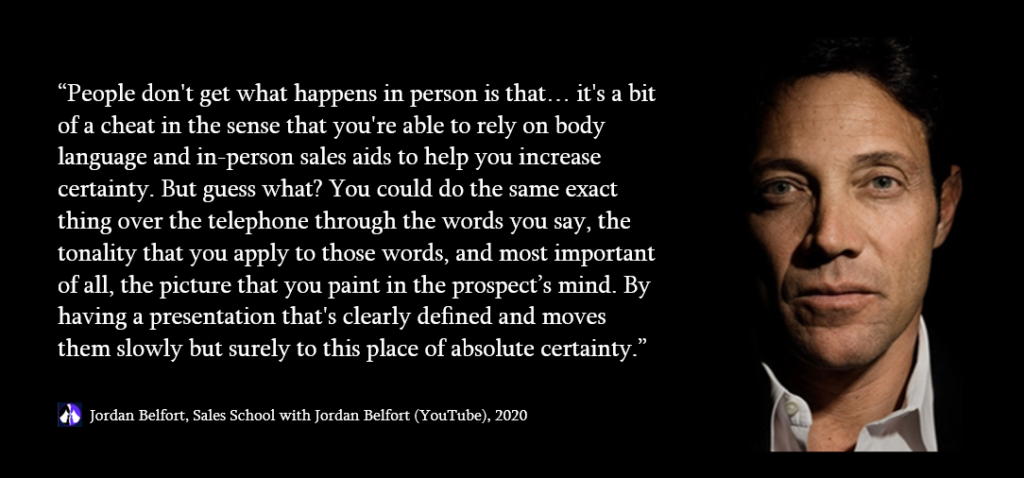

The real wolf of Wall Street — who served 22 months in prison for pleading guilty to securities fraud and stock market manipulation — now models himself as the “World’s #1 Sales Trainer,” selling courses on how to master sales and persuasion techniques “without sacrificing integrity or ethics.” In a YouTube video, Belfort explains the process of turning doubtful prospects into customers using the power of tonality:

Source: YouTube

Body language. Tonality. Painting a vivid picture in someone’s mind. While it’s easy to reduce Belfort’s “Straight Line System” to a conman’s script, these are in fact the exact same techniques a charismatic person would use in order to ace a job interview, nail a public speaking event, close an important business deal, or impress a date.

Society actively encourages and rewards us for exuding this kind of salesy confidence—for knowing precisely how to move a person to “a place of absolute certainty.”

That’s why framing a social action with the right tone and situational label makes a difference in participation and cooperation. Whether you’re working for a small business, a tech giant, or a charity for cancer research, your place of absolute certainty in a business (good, bad or ugly) will inevitably be the bottom of someone else’s wallet. Once you understand this, it’s hard to unsee its imprint in everyday life. As neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky put it: “Call the game the “Wall Street Game,” and people become less cooperative. Calling it the “Community Game” does the opposite.”

Stress and survival

If so much of our behavior can be manipulated — from the way we intonate and pause to how we position our shoulders and direct our gaze — can’t we simply “act our way out” of any situation? Yup, and some of us do it all the time. Look around and you’ll find that the adaptive strategies used by conmen are often the same ones used by body language experts and self-help gurus to teach “strong leadership” and confidence. It’s this adaptive instinct that helps us maintain control and survive under stress. In fact, that’s exactly how a runaway prisoner named Richard McNair managed to get out of a tricky situation with an experienced cop.

In the video, McNair assumes the alias “Robert Jones” (which he accidentally changes to “Jimmy Jones” without raising suspicion), describing himself as a “roofer” who is working in the area with his little brother. A plausible story that provides an alibi for his bleeding knees. When interrogated, he cooperates with the officer — adhering to his requests, answering questions, and feigning total ignorance while in character. As the conversation progresses, McNair establishes trust by casually entering and exiting the officer’s personal space, prompting him to laugh it off as a case of mistaken identity: “You’da run by now, you know that yourself.”

In a letter addressed to journalist Byron Christopher — who later published a book chronicling the life of the three-time prison escapee — McNair reveals the “rational motivation” behind his calculated performance, explaining:

“You have to want it bad. […] I could see the camera in the window of the cruiser. I did realize it was being recorded. Not much I could do. I used a submissive posture in the video. Give him his authority. Shoulders slack, arms loose at side, hands open and visible. Just a guy out jogging and keeping loose while we talked.”

From The Man Who Mailed Himself Out of Jail

In doing so, McNair clearly illustrates “the basic social contradiction out of which the character is built”. On one hand, he uses his intelligence, imagination and physicality to identify with the character of Jimmy Jones, and on the other, stands estranged from the role to study the effects that his performance produced on the audience.

👋 Hey! Know someone who’d like this piece? Share it and start a conversation!

No wonder we’re sometimes in awe of the conman — an actor driven solely by the motivation to survive — whose detached and highly-controlled self-presentation projects the fantasy of a disempowered audience. Yet it’s not the crime or the criminal we applaud; it’s the vicarious pleasure of outsmarting a system designed to control us. In such instances, the con artist may illuminate the many contradictions of our hypocritical world, regardless of their own redemption.

On such occasions, “distance” becomes more persuasive than total immersion. But nowhere is surface acting more evident in daily life than the service and hospitality industry, where displays of emotions become more important than the sincerity with which they’re conveyed. In The Managed Heart, sociologist Arlie Hochschild describes this as “emotional labor” i.e. putting someone else’s emotions above your own in the context of work. Think of flight attendants, baristas, waiters, customer service agents, or y’know, hotel managers…

Wealth and identity

In film and theater, the process of oscillating in and out of character takes enormous training and perspective-taking. The actor may go to great lengths just to empathize with a character whose actions they may not necessarily agree with. It’s a way to reconcile the self with “the Other”.

In everyday life, however, self-deception may be activated unconsciously during fight or flight mode. It’s essentially a stress response.

This is why wealthy people tend to feel more “deserving” of their wealth and believe in hierarchies. According to research, they also tend to have less empathy for the poor — the quintessential “Other” who’s easily ignored through the simple idea: “If I can do it, so can they.” It all adds to the socio-economic tension we see in luxury resorts, usually nestled in the heart of an impoverished “third-world” where being rich feels next to godliness. Stanford neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky explains:

“When it comes to empathy and compassion, rich people tend to suck. This has been explored at length in a series of studies by Dacher Keltner of UC Berkeley. Across the socioeconomic spectrum, on the average, the wealthier people are, the less empathy they report for people in distress and the less compassionately they act. Moreover, wealthier people are less adept at recognizing other people’s emotions and in experimental settings are greedier and more likely to cheat or steal. […] Make people feel wealthy, and they take more candy from children.”

Yep. Welcome to The White Lotus.

The logic of “Us vs. Them” is so crucial to the construction of identity that we’re constantly deceiving ourselves to justify self-serving behaviors at scale. This is explored extensively in the third season of the show, especially through the metamorphosis of the wealthy Ratliff family who must lose all attachments to come to grips with who they are.

In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, show creator and writer Mike White explained this disorienting journey for the parents Tim and Victoria (played sublimely by Parker Posey and Jason Isaacs) — and its latent effects on their offspring:

“Tim has done this shady thing and realizes not only are they going to be poor, but that this idea of this self that he’s created, he’s going to have to rip off the mask and see that he’s not that person. It’s an annihilation of his identity in some deep way where it’s almost like, ‘Why live if you can’t be that person?’ And let’s burn down the entire world instead of having to face this life post this identity. […] Victoria has a superiority complex and it has extended to her kids and it’s turned it into a little bit of a cult where they’re all kind of incestuous, that nobody’s good enough and so they’re all kind of looking inward.”

Inward. Insular. And literally self-obsessed. Self-deception at its richest.

🌟 READ LATER: Get the complete deception series in your inbox for FREE!

Deceiving “down”

When you look up deceit and self-deception, you see a lot about big personalities. But deception isn’t always flashy. Sometimes it’s quiet, polite, unsuspecting. In fact, it even might even make a big show of its own smallness in order to appear non-threatening. Evolutionary biologist Robert Trivers notes this kind of behavior in the animal kingdom:

“We usually think of deception where self-image is concerned as involving inflation of self—you are bigger, brighter, better looking than you really are. But there is a second kind of deception—deceiving down—in which the organism is selected to make itself appear smaller, stupider, and perhaps even uglier, thereby gaining an advantage. In herring gulls and various other seabirds, offspring actively diminish their apparent size and degree of aggressiveness as fledglings, to be permitted to remain near their parents, thereby consuming more parental investment.”

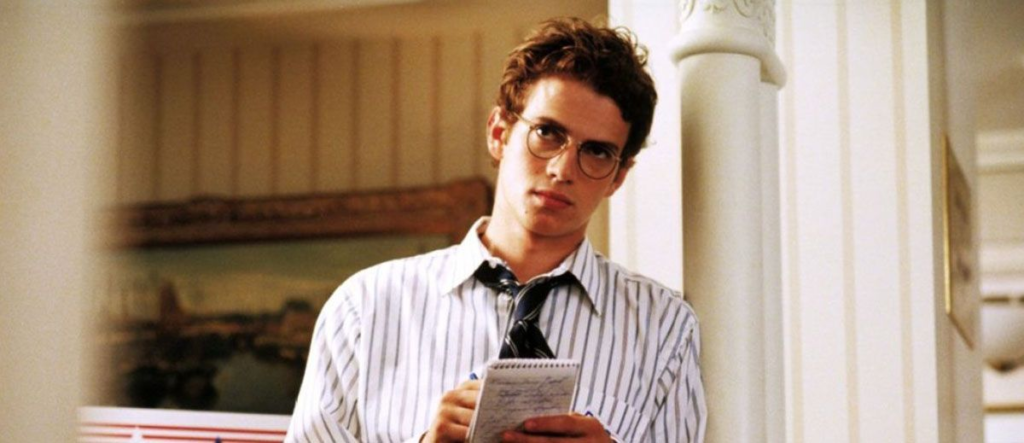

There’s ample evidence of “downward deception” in personal and professional life. We see the latter in Shattered Glass, a 2003 film based on the real-life story of former journalist Stephen Glass who fabricated more than two dozen articles during his time as a 20-something reporter at The New Republic. How? By channeling the self-deprecating nice guy while fabricating his sources. In an appearance on 60 Minutes, the real Stephen Glass explained why he did it:

“I loved the electricity of people liking my stories. I wanted every piece to be a home-run.”

Of course, Glass didn’t become a great storyteller overnight. He watched, took notes, observed people’s insecurities, which gave him enough prompts to elicit desired responses. In the film, his character compliments the receptionist, grabs lunch for overworked colleagues, and downplays important phone calls from Harper’s and Rolling Stone. “It’s probably nothing,” he tells perplexed colleagues, who simultaneously adore and envy him.

So what happens when he starts to slip up? When something about his reporting just doesn’t add up? “Are you mad at me?” he pouts, probing for sympathy like a wounded child. Like all good magicians, Glass builds trusts and diverts the subject’s attention.

• A disciplined performer

For sociologist Erving Goffman, Glass’ short-lived performance would fit the definition of “a disciplined performer” who skillfully moves in and out of tricky situations without betraying his public image (until it collapses on itself):

“And if a disruption of the performance cannot be avoided or concealed, the disciplined performer will be prepared to offer a plausible reason for discounting the disruptive event, a joking manner to remove its importance, or a deep apology and self-abasement to reinstate those held responsible for it. The disciplined performer is also someone with ‘self-control.’”

You might be thinking… if people in ordinary jobs cultivated this level of ‘self-control,’ they’d probably be creepy and potentially sociopathic. Yet in certain jobs, dramaturgical discipline is required to maintain composure in high-stress situations. Think of politicians, lawyers, communication experts, as well as airline pilots, ER doctors, 911-operators, and first-responders. (I know for a fact if I hadn’t channeled my inner monk during a kayaking accident with a friend, we both might have drowned. Unironically, my last words would have been: We should do this stoned.)

Of course, this wasn’t the first time a young journalist played pretend while fabricating stories for a high-profile newspaper. Years later, Jayson Blair came under fire for “inventing or plagiarizing” portions of at least three dozen articles in The New York Times. When a student at Duke University asked why he did it, Blair, who was careful not to stigmatize mental illness, put it bluntly: “I was too arrogant. That arrogance blinded me to a lot of my weaknesses.” This is an excellent example of how self-deception facilitates interpersonal deception, which in turn enables the proliferation of lies on a macro-level.

Lying to yourself

Contrary to sensationalized portrayals of deception in true crime documentaries, we’re constantly engaging with it in some form, especially with ourselves. We know some of this is social-psychological, some to do with our environment and cultural expectations, and some, purely biological. Other times our survival instinct goes berserk. We fear being wrong far more than we care to be right. Or maybe we sacrifice so much for a lie, we desperately need it all to mean something. We all participate in a fiction that helps us navigate our own contradictions.

Go the other way and study every trick in the deception handbook, and now you’re someone who trusts no one and questions everything. But you still don’t have a built-in antenna for “truth”. Just a different system of distinguishing right from wrong, true from false, based on a cynical view of the world. And therein lies the tragedy.

Society can’t function without trust — and deception preys on your need for it. Whether it’s trusting social institutions, groups, relationships or your own intuition, every time you believe in something, you disbelieve the opposite. Self-deception fills itself into this crack.

Even when journalism is reasonably true, fair, and balanced, we — the general public — are victimized by our own propensity for self-deception as we choose sources that affirm personal narratives. Trivers explains:

“However much we champion freedom of thought, we actually spend much of our time censoring input. We seek out publications that mirror or support our prior views and largely avoid those that don’t. If I see yet another article suggesting the medical benefits of marijuana, you can trust me to give it a careful read; an article on its health hazards is worth at best a quick glance. Regarding tobacco, I couldn’t care less. The scientific facts were established decades ago and it has been years since my last cigarette. So this bias in my attention span is both directly adaptive — I smoke marijuana, so I am interested in its effects — and serves self-deception, because I hype the positive and neglect the negative, the better to defend the behavior from my own inspection and that of others.”

Yep, I’m like that about coffee. My friends, about wine. Guess whose self-deception helps them sleep at night — and whose helps them churn out meticulously-researched articles for free.

Thank you for reading. Join the Backstage Newsletter for new posts every week!

🎬 Cool stuff referenced in this piece: The Devil’s Advocate by Taylor Hackford, The Wizard of Lies byBarry Levinson, The Wolf of Wall Street by Martin Scorsese, Sales School with Jordan Belfort (YouTube), The Man Who Mailed Himself Out of Jail by Christopher Byron, The White Lotus by Mike White, Shattered Glass by Billy Ray, 60 Minutes with Stephen Glass, Martha Marcy May Marlene by Sean Durkin, Honey Boy by Shia LaBeouf, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life by Robert Trivers, and The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life by Erving Goffman. Enjoy!

💭 Leave a comment! What’s a lie you tell yourself to cope with the harsh realities of life?