Why Are We So Easily Deceived?

Studying liars may help you understand deception — but won’t protect you from it.

Table of Contents

This is Part 1 of a four-part series on Everyday Deception. Check out the rest:

I’m one of those annoying people who talks during the movies and then shames someone else for doing the same thing. Horror films are even worse because I don’t get scared. I get mad. Which makes me even chattier…

Why on EARTH would you do that with a killer on the loose? ➡️ Scream

Who the HELL sticks their head out of the car window like that? ➡️ Hereditary

How is this S.O.B. still standing after getting SHOT? ➡️ Every film that ever existed.

Despite my overreaction, I’ve probably had more “what-were-you-thinking”-moments in real life than the ill-fated characters of Final Destination. See, I may be a “rational” film spectator, but I am also:

- The idiot who shared my financial details with some stranger over the phone

- The moron who clicked on multiple phishing emails at work (on separate occasions)

- The sucker who got talked into donating to a dodgy charity

These behavioral facts alone could get me bamboozled and axed in the first 10 minutes of any film—let alone one with a psychopath on the loose. Deep down I know I am easily deceived. But my audience-chatter doesn’t result from a lack of self-awareness. It results from a lack of control I feel in my own life (which doesn’t make it any less annoying). While deceiving someone requires a high degree of social skill, being deceived isn’t necessarily a matter of intelligence. It’s a matter of trust—of relinquishing control. That’s what makes the whole thing unpredictable and maddening, both the act of controlling someone and being controlled.

Why do we fall for obvious traps?

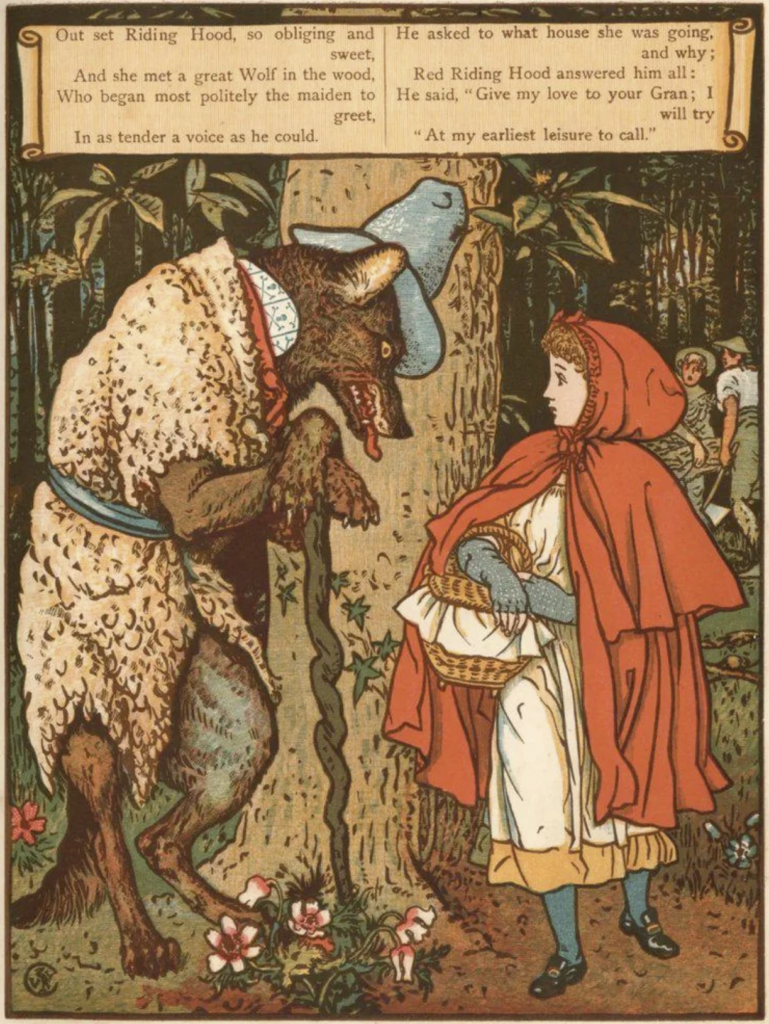

Little Red Riding Hood, 1875, Walter Crane, George Routledge & Sons

• Common sense

No matter how perceptive you are or how many cautionary tales you’ve heard, you’ve probably been fooled and participated in fooling others. We trust when we should probably question, we question when we should probably trust, and we’re easily ensnared by fanged sheep and weird fish.

But why? Why do you have a “weird feeling” about your best friend’s date, but not the duplicitous charmer at the bar? The creep at a children’s party, but not the babysitter you barely know? If something’s too good to be true, it probably is. So why don’t we use common sense when we need it?

For one thing, it’s often through common sense that we lower our guard in the first place. No one in their right mind would share sensitive information with a stranger, right? But what if you got a call from a verified number? A familiar name? From a reputable institution? What if they were acting in your interests? Trying to protect you from a real-time threat—or requesting your help in a crisis? If you can’t rely on the kindness of strangers, how can they rely on yours?

• Stress on the brain

It’s a well-known fact that the brain doesn’t make sound decisions under fear, stress, or social pressure—and when there’s urgency involved, you alleviate some of the stress by placing your trust in someone. We trust in an effort to protect ourselves and/or others. Often that’s the very basis of “common sense” and it’s exactly what happens to victims of a well-orchestrated scam.

Human attention is exhaustible and renowned neurologist Richard Cytowic reminds us we’re not particularly great at considering multiple possibilities at the same time: “We lack the energy to do two things at once effectively, let alone three or five. Try it,” he warns, “and you will do each task less well than if you had given each one your full attention and executed them sequentially.”

When you’re in the midst of a time-sensitive crisis with life savings, social security, or your reputation on the line, you’re suddenly juggling a bunch of hypothetical scenarios with the added pressure of limited time. It’s hard to think you might be getting duped when you’re focusing on something far more dangerous: the possibility of losing everything or someone you care about.

• Real versus fake

This is why even the best of us fall for it, such as the reclusive art collector Virgil Oldman (played by Geoffrey Rush) in The Best Offer. Virgil is no ordinary art collector. He’s a respected auditor who valuates “real” art, secretly manipulating their worth so he can swindle authentic works with the help of a literal partner-in-crime.

When a mysterious woman named Claire suddenly enters Virgil’s life, he has no time for her nonsense… until she begins to exhibit the same qualities as the subject of his secretly swindled paintings. Over time, she shares enough idiosyncrasies to win over his sympathy, his trust, and eventually, his love. Besides, how could anyone keep up a sham for so long?

This level of commitment and long-game approach is particularly common in situations where betrayal occurs through a calculated emotional investment motivated by a principle (“everything can be faked”) or cause — similar to what we see in the 2014 sci-fi Ex Machina. It follows the story of Ava, an AI humanoid robot who manages to convince a skeptical coder that she’s not only human, but one with very real feelings for him.

Just as Claire’s staged emotions are instrumental in accessing Virgil’s vault, Ava’s are essential for her own freedom and survival. How exactly do they pull it off and why do their subjects—sharp, careful, and questioning as they are—ultimately fall for it? While the deceivers’ motives vary, both create a convincing emotional façade that appeals to the subject’s unique profile, coupled with a sympathetic plea for help that obfuscates an obvious danger.

It’s hard to resist a script that writes you out to be a hero.

Then there’s the million-dollar question: was it all a lie? What if Claire was being manipulated? And wasn’t Ava the real victim, trapped between the fantasies of two men? Sometimes our consideration for moral ambiguity makes this knot painfully tight.

Doubt and discernment

Go the other way and refrain from trusting anyone, and now you’re in a different ring of hell. For one thing, if you resist vulnerability in a moment of perceived danger, what else are you willing to gamble? Even the most discerning of us can’t escape the self-flagellation of absolute certainty.

This is what happens in the film adaptation of John Patrick Shanley’s Pulitzer prize-winning play. A parish school principal (played by Meryl Streep) suspects a priest (played by the late Philip Seymour Hoffman) of sexual misconduct with a young boy. An iron-fisted traditionalist, Sister Aloysius is already wary of Father Flynn’s new methods—and now she thinks he’s guilty of a crime he may or may not have committed. Does she have any proof? No. “But I have my certainty!” she tells him after posing a damning question to which there can only be one simple answer.

It’s a masterful film crafted with such delicate ambiguity that you can watch it over and over and still feel a degree of indecision at the end, which I suppose is the whole point of the film. But that’s just me and maybe you’ll think differently. Sometimes I re-watch it and feel convinced about the ending. But the certainty doesn’t last very long. Is it a clue or confirmation bias? I want to be right but I’m afraid to be wrong.

It all makes you wonder how you can be so sure about someone, public or private—and how simultaneously audacious and vulnerable that instinct can be.

When news broke out about Harvey Weinstein’s sexual harassment allegations—and the 75 women who came forward—many people starting questioning his professional relationships and the famous names he’d been associated with over the years. Did they know? Did their silence make them complicit? One of the names that came up was, of course, Meryl Streep who regrettably referred to him as “a god” in a Golden Globes speech. In an interview with The New York Times, Streep, who was a force in Doubt, now ironically found herself reflecting on her own experience with an accused predator and how his mask eluded her:

The shock can be even more disorienting if it’s tied to someone closer to you than a colleague or a boss. Like a family member or a partner. It’s so much easier to ignore something in the absence of concrete evidence—yet denial can act as a laxative for a truth we simply can’t stomach in the moment. To make matters more complex, deception isn’t just “a very deep feature of life,” it’s also necessary for the survival of our species. Robert Trivers, sociobiologist and author of The Folly of Fools explains:

“When I say that deception occurs at all levels of life, I mean that viruses practice it, as do bacteria, plants, insects, and a wide range of other animals. It is everywhere. Even within our genomes, deception flourishes as selfish genetic elements use deceptive molecular techniques to over-reproduce at the expense of other genes. Deception infects all the fundamental relationships in life: parasite and host, predator and prey, plant and animal, male and female, neighbor and neighbor, parent and off-spring, and even the relationship of an organism to itself. […] Predators gain from being invisible to their prey or resembling items attractive to them—for example, a fish that dangles a part of itself like a worm to attract other fish, which it eats—while prey gain from being invisible to their predators or mimicking items noxious to the predator, for example, poisonous species or a species that preys on its own predator.”

👋 Hey, you sophisticated skeptic! Know someone who’d like this piece? Share it and start a conversation!

As much as we’d like to believe in our ability to distinguish “real” from “false,” we’re not equipped to do so consistently and accurately in a world that mostly rewards, but sometimes punishes, those willing to take things at face value. This is further complicated by the fact that sometimes we get carried away by our own lies, to the degree that we end up believing the ones intended for others. Like claiming to be healthy while devouring an entire pizza. Or claiming to know the truth about something we never witnessed.

Every now and then, we all choke on a lie.

Sociologist Erving Goffman described this kind of role immersion as “inward belief” in one’s own act, contrasting it with role distance which is the ability to see through one’s own act by being in “the best observational position.” While role distance allows us to seamlessly switch from one part to another, it’s a position I personally find near-impossible to assume round the clock without losing my sense of play and sanity. There’s nothing like the hell of constant self-vigilance…

Closeness to the subject

“‘First of all, my dad would have voted for Obama a third time if he could’ve. Like, the love is so real.” (Get Out, 2017)

Gaining trust is such a fundamental part of human interaction that we often say and do things we don’t necessarily mean in order to keep people at ease—and more likely to comply with us. The waitress shows interest in your day just as she hands you the check. Your boss finally acknowledges your hard work only to reveal, “No raises this year.” I tell you how good-looking you are while reminding you to subscribe to my newsletter. I mean you’re probably stunning, but I can’t confirm unless you’ve subscribed (in which case, hello, gorgeous!)

We communicate this way not necessarily to control others, but to negotiate with them during an awkward social transaction. Not only does the reciprocal nature of human interaction make us all susceptible to deception, it also makes us complicit in the process of negotiation that drives social interaction.

Sure, it’s easy to be the voice of reason when you’re not directly involved in the situation. Like listening to a heartbroken friend who’s been cheated on, or reading the news. But you’re not intuiting things out of thin air—you’re in the perfect observable position, removed from the event but attuned to the big picture. When you’re in the situation, you just don’t have that kind of perspective. That’s why, in the film Get Out, Chris doesn’t suspect Rose until he discovers photographic evidence of her disturbing past.

In life, as in art, there are always efforts being made to direct your gaze. Even when watching a film, for instance, the genre alone informs you how to respond as a viewer. Horror = This stranger could be a psychopath. Comedy = This stranger could be your best friend. Romance = This stranger could be the love of your life.

That’s why genre-bending stories can be so refreshing and intellectually stimulating. Unless you’ve seen the trailer or read the synopsis, you don’t really know what to expect or where the story might go—which is more representative of “the genre of life.”

Part of the joy (and discomfort) of watching a film is the element of surprise. It’s the unanticipated revelation of our own private pain and anxiety, maybe even our own cruelty and sadism, that makes it deeply personal. Sometimes we start interrogating the characters only to end up interrogating ourselves. This is why film trailers can be so polarizing.

Some spectators can’t stand the fact that they give away the entire plot. Others enjoy it for that very reason because your brain now knows where to look for twists and turns, activating the reward and gratification center as you anticipate those moments on screen. “See, I told you!” we like to exclaim, pleased with our “No shit, Sherlock”-levels of discernment groomed by a tell-all trailer.

Third-party perspective

A huntsman came past, and bethought himself, “How can an old woman snore like that? I'll just have a look to see what it is.” He went into the room and looked into the bed; there lay the wolf. “Have I found you now, old rascal?" said he. “I've long been looking for you.” He was just going to take aim with his gun, when he bethought himself, “Perhaps the wolf has only swallowed granny, and she may yet be released.” Therefore he did not shoot, but took a knife and began to cut open the sleeping wolf's maw. When he had made several cuts, he saw a red hood gleam, and after one or two more cuts out skipped Red Hood, and cried, “Oh, how frightened I have been; it was so dark in the wolf's maw!”

“Little Red Hood,” A. H. Wratislaw, Sixty Folk-Tales from Exclusively Slavonic Sources, 1889

What does all of that have to do with deception in real life? Well, your perception of an event, like a heated argument with a partner or a romantic memory with them, might change drastically depending on how much “distance” you’ve had from it and what’s revealed out of scope. It’s this adjustment to your “depth of field” that ultimately reveals a fuller picture, once we become the spectator of our own life.

In real life, there’s no way you can suspect someone’s out to get you if they already have your complete trust and loyalty. Like a partner, a close friend, a mentor or a guardian. You’re simply too close to the subject. The deception that occurs through these roles is by far the most damaging and the most difficult to detect because it often demands a kind of unreasonable suspicion that can only reasonably surface through a third-party observer. Like the protagonist’s best friend in Get Out.

Stand a little too far from the subject and now the vision’s a little too blurry—allowing you to project meaning on an amorphous blob of a situation that could either look like loving interracial acceptance… or, in the words of Rod Williams, “some sex slave shit.” So how do we adjust our depth of vision to better detect deception in our personal and professional life? How far is too far and how close is too close?

➡️ PART 2: Your Intuition

🌟 READ LATER: Get the complete series in your inbox for FREE!

🎬 Cool stuff referenced in this piece: Little Red Riding Hood by Walter Crane, Weird Fishes by Radiohead, The Best Offer by Giuseppe Tornatore, Ex Machina by Alex Garland, Doubt by John Patrick Shanley, Interview with Meryl Streep in The New York Times, The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life by Robert Trivers, Judith by A Perfect Circle, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life by Erving Goffman, Get Out by Jordan Peele, and Little Red Hood by A. H. Wratislaw. Enjoy!

💜 Thank you for supporting my work. If you like what your read, subscribe for new posts every week!